Long-Sought Protein Structure May Help Reveal How 'Gene Switch' Works

NIST, Brookhaven Researchers Use Tuberculosis Bacteria to End 25-Year Quest

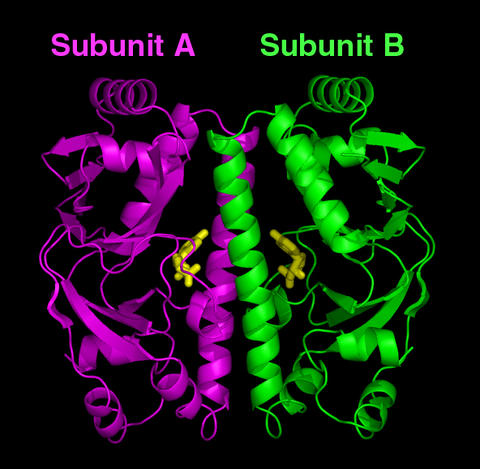

Computer model of the predicted structure for the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) found in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. After binding cyclic AMP molecules (the yellow bodies in the center), the CRP is believed to change its structure so that the two subunits (colored purple on left and green on right) become symmetrical (identical in shape). This the on state of the CRP that can bind a gene (DNA) and activate it to carry out functions necessary for the microbe's survival.

GAITHERSBURG, Md.—The bacterium behind one of mankind's deadliest scourges, tuberculosis, is helping researchers at the Commerce Department's National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) move closer to answering the decades-old question of what controls the switching on and off of genes that carry out all of life's functions.

In a Journal of Biological Chemistry paper posted online this week, the NIST/BNL team reports that it has defined—for the first time—the structure of a "metabolic switch" found inside most types of bacteria—the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein, or CRP—in its "off" state. CRP is the "binding site" (attachment point) for cAMP, a small molecule that, once attached, serves as the signal to throw the switch. This "on" state of CRP then turns on the genes that help a microbe survive in a human host.

The researchers hope that once the switching mechanism is understood the data can be used to develop new methods for preventing tuberculosis and other pathogenic bacterial diseases.

"We know that many pathogenic bacteria use cAMP as a signal for activating genes that keep the microbes thriving in adverse conditions, and therefore, remaining virulent," says NIST biochemist and lead author Travis Gallagher. "Blocking these processes might provide ways to shut down infections and save lives."

Additionally, the researchers believe that learning how this specific protein switch works may provide insight into how genes in general are regulated.

The biochemical puzzle surrounding the CRP switch is the mechanism by which the protein binds cAMP at one end, then attaches to—and activates—a gene (DNA) at the other end. Believing that the protein somehow changes its overall shape after binding cAMP, researchers set out 25 years ago to study the structure of CRP in both its active state (with cAMP bound to it) and inactive state (without bound cAMP) to document where the morphing occurs.

Unfortunately, the task proved to be extremely difficult. Using CRP from the bacterium Escherichia coli, researchers were able to crystallize the protein in its active ("on") state and examine the structure using a technique called X-ray diffraction. However, the structure of the inactive ("off") E. coli CRP eluded them as attempts to crystallize it repeatedly failed. With only the structure of the "on" state defined, the genetic switching mechanism remained a mystery.

The breakthrough was achieved when Gallagher; NIST colleagues Prasad Reddy, Natasha Smith and Sook-Kyung Kim; and BNL's Howard Robinson substituted the CRP from Mycobacterium tuberculosis [the pathogen that causes tuberculosis] for the E. coli protein.

The team's initial success—obtaining crystals of CRP in the "off" state—was dramatic given that no one had accomplished the feat in nearly three decades of trying with E. coli. But the real excitement came when the crystals were examined with X-ray diffraction.

"Although the M. tuberculosis protein in the 'off' state consists of two subunits that are genetically identical, we were surprised to see that the subunits were not structurally symmetrical as well," Gallagher says. "In most two-subunit proteins, each subunit has the same conformation as the other."

Gallagher says that the NIST/BNL team theorizes that it is the asymmetry in the absence of cAMP that prevents the protein from attaching to DNA. This, in turn, keeps CRP from activating genes when they are not needed.

"Our next step is to crystallize M. tuberculosis CRP in the active state and define its structure," Gallagher says. "When that is accomplished, we'll be able to see the identical protein from the same organism in both states, which may give us the means to explain how CRP switches from its asymmetric form [inactive state] to its symmetrical [active state] form."

The work detailed in the Journal of Biological Chemistry paper was performed at the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute (UMBI)'s Center for Advanced Research in Biotechnology (CARB), a partnership among UMBI, NIST and Montgomery County, Md., that advances biotechnology by integrating chemical, physical and biomolecular sciences through research on biomolecular structure and function, systems biology and biometrology, and through the development of new technologies for measurement, analysis and design.

As a non-regulatory agency, NIST promotes U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve our quality of life.

D.T. Gallagher, N. Smith, S-K Kim, H. Robinson and P.T. Reddy. Profound asymmetry in the structure of the cAMP-free cAMP receptor protein (CRP) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry (published online Feb 4, 2009).