Cybersecurity Insights

a NIST blog

Protecting Model Updates in Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning: Part Two

The problem

The previous post in our series discussed techniques for providing input privacy in PPFL systems where data is horizontally partitioned. This blog will focus on techniques for providing input privacy when data is vertically partitioned.

As described in our third post, vertical partitioning is where the training data is divided across parties such that each party holds different columns of the data. In contrast to horizontally partitioned data, training a model on vertically partitioned data is more challenging as it is generally not possible to train separate models on different columns of the data (but overlapping rows) and then compose them afterwards.

Instead, we need methods to be able to train on the collective data while protecting the privacy of that data. One critical step required for this is privacy-preserving entity alignment: matching corresponding records (e.g. records referencing the same person) across different datasets. Parties can use the result of the entity alignment to train a model in a similar way to how they would in a horizontal partitioning scenario.

Matching corresponding records without revealing the records themselves is a challenging task. In the remainder of this blog, we discuss two methods for privacy-preserving entity alignment: private set intersection and Bloom filters.

Private set intersection

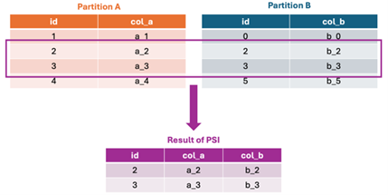

A private set intersection (PSI) is an input privacy technique that enables data linking between parties. The result of a PSI process reveals information to the participants only for rows of data that match on a common key. This is illustrated in Figure 1. For example, a pilot research project led by researchers at Georgetown University applied PSI to link U.S. Department of Education data with data from the National Student Loan Data System to compute financial aid statistics without revealing students’ social security numbers.

Some PSI approaches reveal only the number of matching rows, while others reveal more information (e.g. the contents of matching rows, as in the example in Figure 1). PPFL systems often rely on the contents of the matching rows, and must therefore use “leaky” PSI approaches. There are also some trade-offs to consider between the strength of a PSI technique in protecting data against its performance when applied in federated learning scenarios on large data sets such as those in the UK-US PETs Prize Challenges.

Bloom filters

A second approach to entity alignment is to construct a Bloom filter---a probabilistic data structure that uses a collection of hash functions to enable efficient storage and lookup of elements. Since Bloom filters are probabilistic, they sometimes make mistakes (false positives).

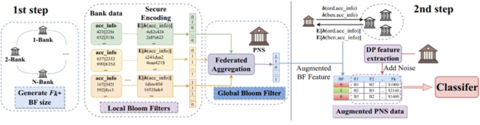

In the context of PPFL, Bloom filters can also provide privacy benefits. Specifically, the false positives provide a kind of input privacy protection automatically. Some PPFL systems use Bloom filters to facilitate privacy-preserving feature mining—a process that determines which attributes of the data to use when building the model. This was the approach used by Scarlet-PETs, a winning team from the US side of the UK-US PETs Prize Challenges. Their solution is shown in Figure 2.

In the first step, feature mining is carried out locally at each bank to create local Bloom filters containing accounts that are deemed potentially suspicious based on the account-level data. These local filters are aggregated into a global Bloom filter, which is used to augment the payment network transaction data. Since Bloom filters are represented as strings of bits, they can be aggregated using the techniques described in our fourth post. Finally, the payment network adds an additional binary field “BF” to the transaction data, which is 1 if either the sending or receiving account for the transaction is present in the global Bloom filter, and 0 otherwise. This completes the entity alignment step, and a (differentially private) classifier can then be trained on this augmented data.

The use of Bloom filters helps protect input privacy as there is no direct data sharing between the different parties; only information regarding the potential presence or absence of a specific feature is revealed, not the actual content of the data itself. However, it may still be possible for sensitive data to be leaked via a Bloom filter. In the example above, the global Bloom filter is shared with the payment network. Depending on the accuracy of the filter and how it has been constructed, it may be possible for the payment network to learn some information about the bank data that they should not. At minimum, in this setup the payment network is able to learn that for transactions where BF = 1 there is a high probability that one of the banks has flagged either the sending or receiving account (or both) as suspicious. In the real world, a policy decision would need to be made between the banks and the payment network to determine whether such data leakage would be permissible.

Balancing performance with leakage

The techniques described in this post provide efficient methods for performing entity alignment with input privacy in PPFL, but they both leak some information about the private data involved. In the case of PSI, the system may leak information about the number or even the contents of matching rows; in the case of Bloom filters, the system will leak (noisy) information about the matching status of each row. It’s possible to layer additional techniques on top to eliminate this leakage such as secure multiparty computation, fully-homomorphic encryption, or secure enclaves---but as discussed in our fourth post, these techniques often carry a significant performance cost.

System designers must carefully consider the leakage of these techniques as part of the system’s threat model—the description of attackers the system is supposed to defend against. In some cases, the additional leakage poses little privacy risk, and it may be acceptable to use PSI or a Bloom filter as part of the system. In other cases, the leakage poses major privacy risks, and requires the use of additional techniques. Balancing the privacy risk of information leakage against the performance cost of preventing those leaks remains a significant challenge in vertical federated learning.

Coming up next

In our next post, we’ll turn our attention to output privacy, discussing approaches that can prevent an adversary from reverse engineering anything about the training data from a trained model.