Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

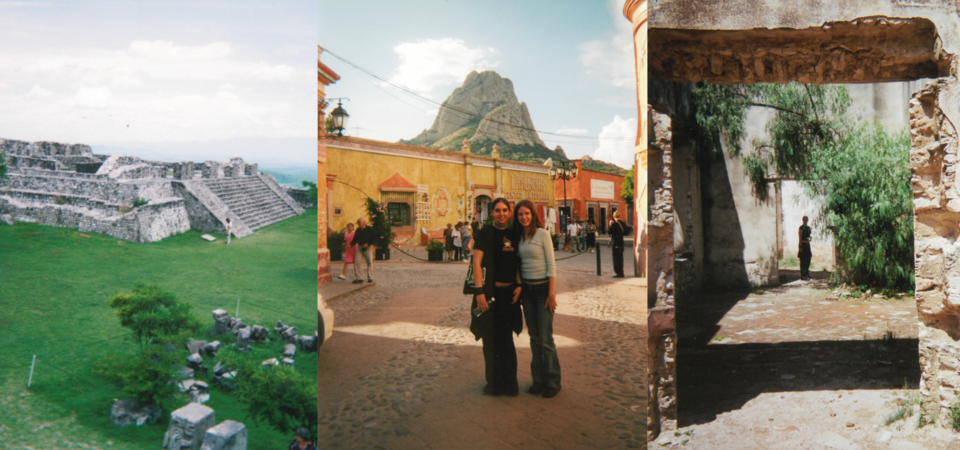

Some photographs of my cousin and me in 2002 exploring historic towns and ruins in the Mexican countryside.

This month, we celebrate the heritage of the multitude of identities that arose from the intermingling of Spanish and indigenous American cultures. To do this, we’d like to reflect on the rich cultural advances of the indigenous people whose measurement science helped fuel the development of pre-Columbian civilizations and whose blood still flows through many of today’s Hispanic Americans. This post is in no way a comprehensive account of all the measurement systems existing in pre-Columbian societies of the Americas.

As a child growing up in Fairfax, Virginia, I used to play archaeologist by digging for ancient artifacts in my backyard. This may come as a surprise, but I never dug up anything culturally significant; rather, my finds were limited to rocks, sticks and mud (which, coincidentally, could be used to make some pretty spectacular mud cakes). Why did I have this crazy notion that I might find something more interesting? One day while visiting my grandfather’s house in Mexico City, my father had pulled an old shoebox out of his childhood closet and opened it to reveal the Aztec artifacts he had dug up in his own backyard when he was my age. I held the tiny figurines in the palm of my hand, marveling at their intricately carved features, weathered by time.

From the myriad artifacts and structures left behind by ancient pre-Columbian civilizations, alongside the observations of the Spaniards who first arrived in the New World, historians have been able to piece together an understanding of the complexities of pre-Columbian measurement systems. “[They] have measures for everything,” the historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas wrote about the indigenous people of Mexico in his 1601 description of Hernán Cortés’ observations.

This is not surprising, considering their monumental achievements in fields such as engineering, architecture, astronomy and medicine. If you had walked through the bustling Aztec market Tlatelolco (in present-day Mexico) before European contact, you would have encountered an orderly and well-regulated measurement system. Although Aztecs appear to have never used scales, they used numbers of easily countable items and volumes of specific commodities to facilitate trade. For example, they used a quauhchiquihuitl — a wooden box subdivided into divisions as small as one-twelfth — for the purpose of measuring corn and other dry goods. They also produced leather bags, cups and jars of graded sizes for measuring dry and liquid goods, such as cocoa beans, resins, water, honey and oils. To prevent the duplicitous exchange of goods, inspectors patrolled open-air markets with the power to punish swindlers, destroy faulty measures, and mark accurate measures with a seal. Clearly, accurate measurements were highly valued.

As European contact was first taking place in Mesoamerica, the Andean civilizations of South America, in an area including modern-day Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile, were thriving. In the Inca empire, the last of the Andean civilizations, measurements evolved very differently from the Aztec. Although the Incas did develop and employ scales, there is no evidence that resulting measurements were relative to a standard; rather, goods were likely weighed in relation to other goods. The Dumbarton Oaks library in Washington, D.C., has in its pre-Columbian art collection two examples of Incan scales (Chimu-Inca Balance-Beam Scale, Lambayeque Weighing Balance), the intricate decoration of which is a testament to the importance these civilizations placed on measurement and trade.

Throughout human history, the development of measurement systems has gone hand in hand with the development of numerical systems. Pre-Columbian civilizations were not an exception. Aztecs developed a base 20 system (where things are counted in groups of 20) — of which we have evidence through extensive mathematical writings in ancient codexes — and Incas developed a base 10 one. The Inca didn’t develop writing (at least, not in the way we know it); rather, they established a system based on arrays of knotted cords known as quipus to record numbers, metrological units, and calculations in a decimal system.

The architectural and engineering feats such as pyramids and aqueducts of pre-Columbian cultures that still impress and mystify tourists to this day wouldn’t have been possible without the development of precise length measurements. These ancient structures were constructed of huge stone blocks, some weighing as much as 100,000 kilograms (220,000 pounds), that were placed in such intimate contact with neighboring stones that the blade of a knife cannot be inserted into many of the joints.

For designating measurements of length, pre-Columbian societies developed units that primarily related to the human body. Smaller distances were defined using body parts such as fingers, palms and feet. Incans most commonly used the ricra, the fingertip-to-fingertip distance of outstretched arms (i.e., wingspan). In Aztec society, the tlacaxilanti was a measurement stick developed from the distance from the navel to the ground (a distance which is coincidentally similar to the meter). Larger distances were typically defined in relation to a human’s pace: The Incans provided long distances in either thatkiys (the number of paces) or in terms of time required to walk that distance. Interestingly, a thatkiy (a single pace) and ricra (wingspan) are of similar distance, and yet for long distances, Incans employed thatkiys, as they could more easily be measured (i.e., by using the human body as a measurement tool through the action of walking).

The use of the human body to define length seems to be a ubiquitously human concept used by civilizations around the world. The ability to develop the notion of measurement through a conceptualization of “the self” as a type of standard speaks to the ability of early societies to apply this concept to larger scales and to the grandiose projects requiring those scales.

By applying their ingenuity to the needs of their time, pre-Columbian societies developed systems of measures that allowed for a bustling economy and a rich culture of art and architecture. Upon the arrival of the Spanish to the Caribbean in 1492 and mainland Latin America in 1500, the value of the goods and riches exchanged in pre-Columbian markets was quickly recognized. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec, Maya, Inca and other civilizations devastated these indigenous societies and precipitated a new era of Spanish dominance over their way of life.

Hernán Cortés issued an ordinance in 1525 to regulate and implement Spanish weights and measures, and this was followed in 1536 by ordinances by Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza referring to land measures using the Spanish vara, a unit of measure akin to the yard or meter. Subsequent centuries exhibited a melding of indigenous and Spanish traditions. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the metric system was formally implemented in individual Latin American countries in the effort to ease trade with the global market.

Throughout these centuries of cultural and technological change, those Aztec artifacts my father collected rested deep below the soil (well, not so deep that a child couldn’t eventually find them). Likely, many more artifacts lie beneath the earth in Latin America, waiting to be uncovered so they can continue to tell us the stories of the ancestors of so many Latin Americans, and perhaps in the future more clues about pre-Columbian weights and measures will be revealed.

*edited 9/19/19 to correct the date the Spanish landed in mainland Latin America from 1502 to 1500; and to remove a reference to an ambiguous measurement unit, the netlatolli.