Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

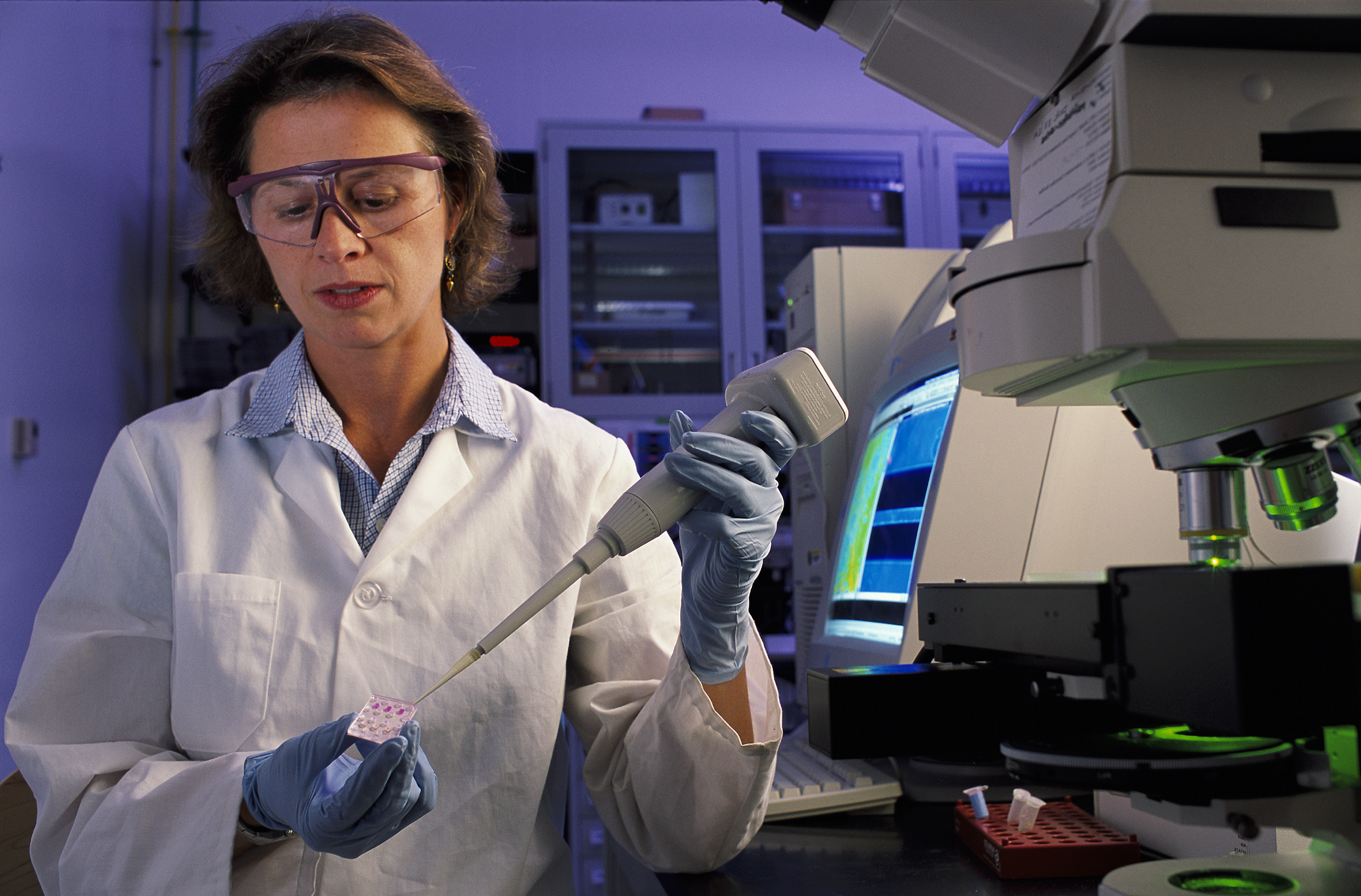

One of NIST’s Most Prolific Inventors Is Also Our Director — and She’s Still an Inventor at Heart

Before she was the director of NIST, Laurie E. Locascio invented materials that make us healthier.

One area of focus for her research was microfluidics. Microfluidics — the science of moving liquids through small spaces — is a vital part of medical treatment and vaccine development. The devices Locascio and her colleagues created helped pave the way for the research that brought us the COVID-19 vaccines (and many other vaccines that are currently in development).

Locascio also helped invent new approaches to medicine and vaccines using lipid nanoparticles, which are fatty “envelopes” that can deliver RNA or other medicines to our cells.

In honor of National Inventors Month, the Taking Measure blog asked Locascio about her background as an inventor and what makes NIST a home for innovation.

How did you get into bioengineering? What did you love about it?

I got into bioengineering circuitously. I was a chemistry major in college, and I started taking some biology and biochemistry courses. I fell in love with that aspect of chemistry, leaning more toward the health care area.

When I was looking for a graduate school, I found there was a very new field at that time called bioengineering. There were only a couple of graduate programs in the U.S. The University of Utah was developing the first artificial heart. So, I decided to go there, and it was a really fun field I had never heard about before because it was so new.

I was hired at NIST right after that. They were looking to hire some researchers in bioscience and bioengineering at the time, so I came to NIST and started a program here.

Can you describe some of your inventions and their role in science and bioengineering?

I had a really prolific, wonderful, energetic and diverse group of researchers in my laboratory around 2000. There was so much energy and so many ideas. That’s when most of my inventions were born, out of the collaboration with such a great group of people.

One of the inventions with Wyatt Vreeland, Michael Gaitan, Andreas Jahn and Joseph Reiner was around the development and formulation of new therapeutics using lipid nanoparticles. So, it was a lipid nanoparticle formulation.

That turned out to be really important because that’s how the COVID-19 vaccines were created, using that approach to the formulation of those therapies. Some of the early instruments for making the COVID-19 vaccines were based on some of the patents we had developed here at NIST.

I also had a lot of early patents around the development of polymer microfluidics. Microfluidics was a very young topic in the late 1990s. Our group got into microfluidics at a time when they were mostly being developed in silicon or glass.

We decided we were going to make them cheaper and more disposable because the medical field needed less expensive approaches to therapies. We started working in the field of polymer microfluidics, and it really took off. A lot of the early patents with David Ross, Tim Johnson, Michael Gaitan and many others were on the development of microfluidics. Today, the most common microfluidic devices used in medicine are made in polymers and not glass. We were one of the first to do that.

What’s the invention you’re most proud of?

I have 12 patents, and they’re all my favorites for different reasons.

In addition to the lipid microfluidics formulation, another invention I worked on was studying chemotaxis with Javier Atencia. That’s basically studying the migration of living cells toward a chemical attractant. Javier spun off a company based on these patents. The technology looks for the presence of bacteria in food. That was also a really exciting time in my career.

I think some of the very fundamental studies of chemical separations in microfluidic systems with David Ross were fun projects, too.

What are some of your favorite parts of the invention process?

I love being an inventor! It feeds my soul. The idea is that you sit in a room and brainstorm with a bunch of supersmart people who are all working toward figuring out what the next great idea is. That is so much fun.

The hard part is trying to make it happen in the laboratory. That takes a lot of perseverance. When you finally get here, and you think, “I think we’ve figured this one out.” Those are great moments. The first brainstorming and then the ultimate “we did it” moment are the two wonderful parts of being an inventor.

NIST is home to a lot of inventors. What makes this organization so supportive of innovation?

I think we have some of the smartest, most creative researchers here that I’ve ever met.

When you’re in academia, you have to write proposals to feed your research. Here, our experts have most of that research funding built into our budget, and that hopefully gives them some freedom to explore, to color outside the lines, to think creatively.

How did being an inventor impact you?

Those creative years when most of my inventions were born were some of the most fun and exciting times of my life.

Years later, I still have a running list on my phone of invention ideas that I come up with. One day, I’ll make some of these ideas happen. If I’m driving, I may get an idea about traffic lights or how to make a better dog leash. I think constantly about what I can create.

When I was inventing in the lab, I got trained to think about what would make people’s lives better. How can I create something to fix that problem? My brain continues to work that way to this day.

What advice would you give to aspiring inventors?

Surround yourself with really smart people. The more you collaborate, the more good ideas will come into your brain. Hearing your own research from other people’s perspectives can really make you start to think differently. And talk to people in different disciplines. Let them open up your mind to new ideas.

Do you ever invite people with ideas to come and share them with you?

sa