The cone snail engulfs and digests the fish.

NIST Cone Snail Research: Milking Killer Mollusks for Medical Answers

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Hollings Marine Laboratory in Charleston, South Carolina, are studying cone snail venom for potential use in medical treatments. The venom is thought to be one of the most powerful toxins produced in nature. To understand how it works, chemists “milk” captive snails and examine the venom’s molecular structure, looking for ways to harness its power in positive ways. Their findings may lead to treatments for a wide variety of ailments, including Alzheimer’s disease and nicotine addiction. Learn more about NIST's cone snail research.

Milking a cone snail for venom can be a delicate negotiation, involving the offering of a goldfish.

In the wild, cone snails harpoon their prey as it swims by. In the lab, the cone snail has learned to exchange venom for dinner. Here, a snail extends its proboscis and discharges a shot of venom into a latex-topped tube.

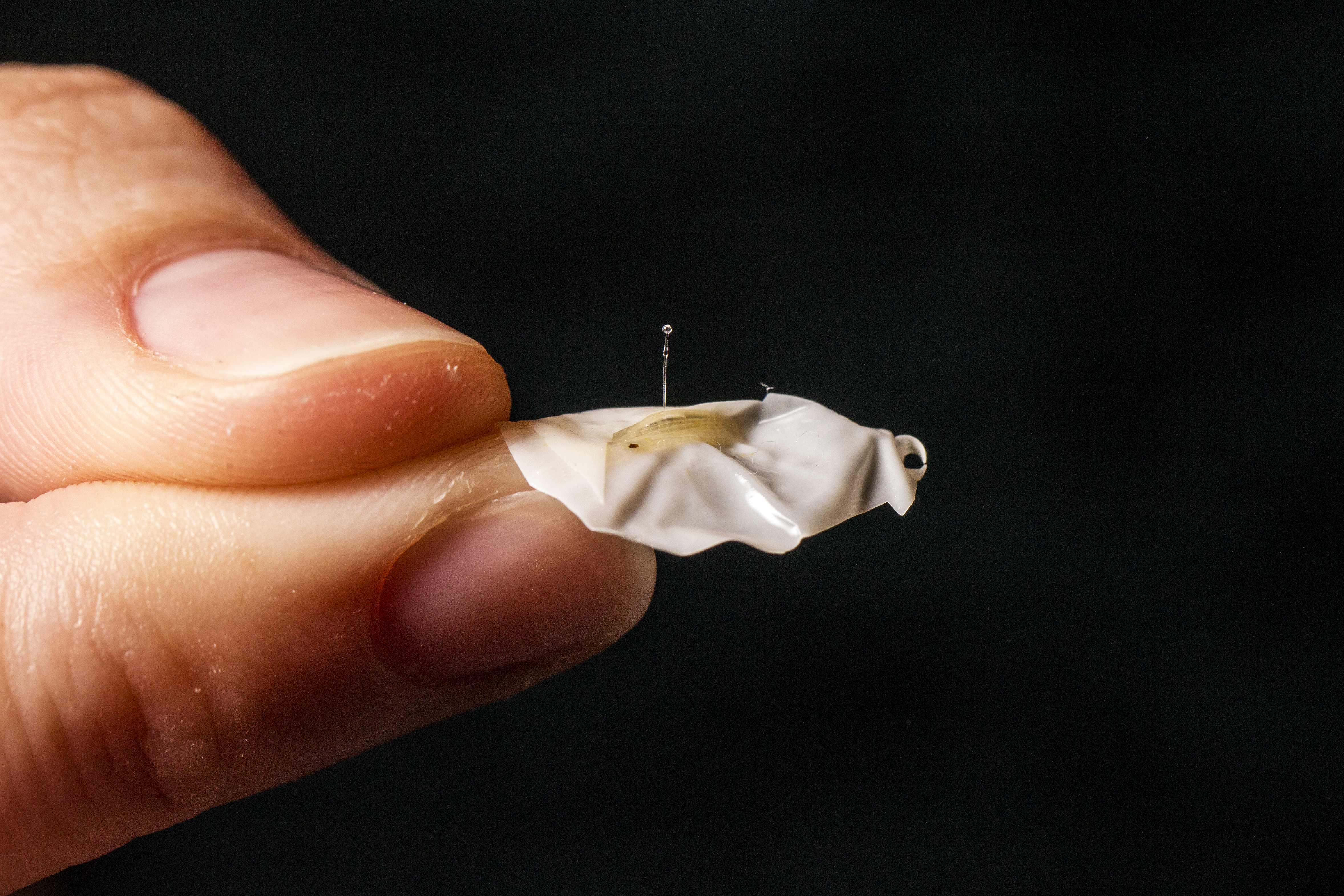

A close-up of the latex seal from the top of the tube, just after venom has been gathered. Note the beige, harpoon-like radula, which was left behind by the snail during the milking process.

Student Mickelene Hoggard (Florida Atlantic University) gives the milked snail its reward, a goldfish.

The cone snail engulfs and digests the fish.

Scientists Carolina Möller (Medical University of South Carolina) and Frank Mari (NIST) observe a cone snail during a recent milking session.

Students Mickelene Hoggard (Florida Atlantic University) and Meghan Grandal (Medical University of South Carolina) work to identify a specimen from NIST’s cone snail group before feeding it, using a lab reference book.

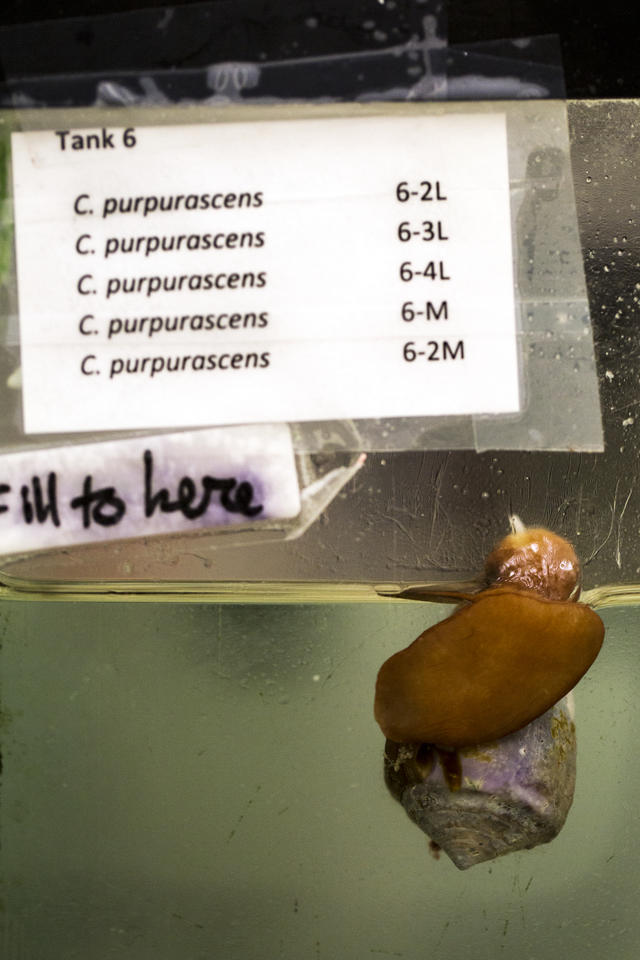

Researcher Carolina Moller from the Medical University of South Carolina checks on some of the 60 cone snails — representing 12 species — kept at the Hollings Marine Laboratory.

In addition to the purple cone snail (Conus purpurascens), the lab has species such as this orange and brown type native to Hawaii, Conus striatus.

The purple cone snail is a common species, although rarely seen in the wild due to its nocturnal habits. It is not considered threatened or endangered in the wild.

Underside of a cone snail in a glass dish. To the left is the siphon, which is where water flows into the cone snail for detection of prey, respiration, and reproduction.