Trial by Fire: A Look at NIST Fire Testing Through the Years

Fire testing may have started some 2.5 million years ago when one of our ancestors stuck his hand into the first flame and “scientifically” determined that the temperature was too hot to bear. Since that primitive beginning, humans have been on an unending quest to understand, measure and exploit the behavior of fire — and most importantly, to improve our ability to protect life and property from its ravages. Fire testing at NIST, a staple of the agency’s research since the early 1900s, has helped provide much of the data, insights and knowledge demanded by that pursuit. Find out more about NIST's fire research and the National Fire Research Laboratory.

NIST conducted what may have been America’s first full-scale fire test when researchers burned down two condemned buildings in Washington, D.C., on June 17, 1928. Data from this experiment, along with previous work by pioneer fire researcher Simon H. Ingberg, eventually led to uniform fire resistance standards for buildings.

Gas and flames erupt nearly 100 meters (300 feet) from a NIST concrete bunker during a 1940 test to define safe and effective storage practices for flammable nitrocellulose films. A vault inside the bunker simulated a typical storeroom, with the charred film reels left behind after the burn proving that fire posed a safety, as well as a preservation, hazard.

To evaluate the fire resistance of all-aluminum staterooms proposed for the luxury liner SS United States, NIST set a full-scale replica ablaze in 1950. The test — designed to simulate the experience of three women traveling to Europe who ignited spilled whiskey with a dropped cigarette — proved that aluminum could prevent flames from spreading for a short time.

Cross piles of wood were burned and studied in this 1961 experiment to model the development and growth of fires in full-size buildings.

In 1975, NIST conducted three full-scale tests of fire and smoke behavior in a Washington (D.C.) Metropolitan Transit Authority bus after a series of suspected arson incidents.

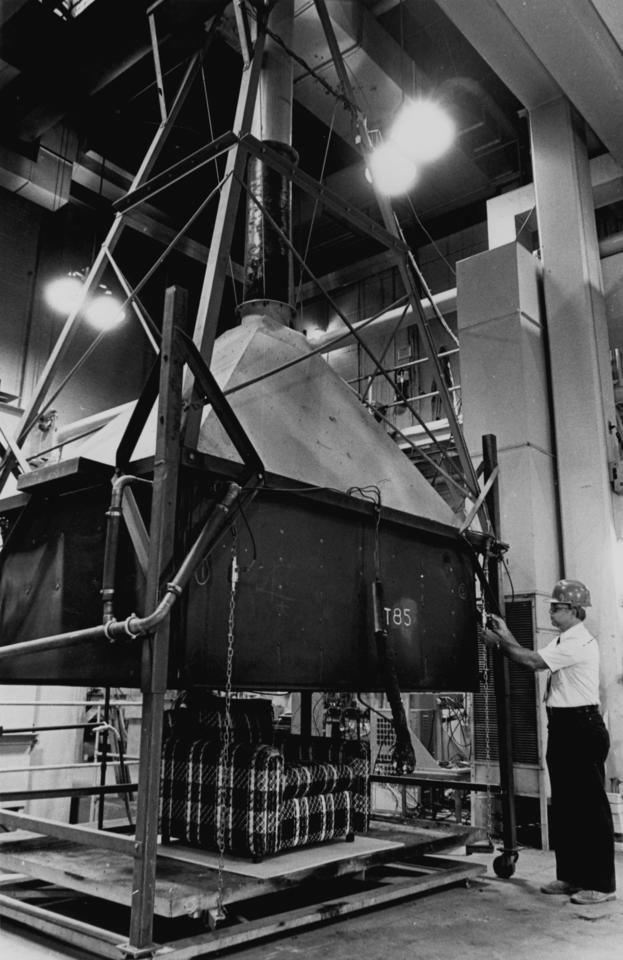

A fire engineer adjusts instrumentation before a 1983 experiment using the furniture calorimeter, a NIST-developed device that measured the rate at which heat was released from burning sofas, chairs and other office and residential furnishings.

NIST engineer Greg Linteris flew aboard two space shuttle missions in 1997 to study soot formation, the shapes of flames, and combustion of chemical droplets in microgravity.

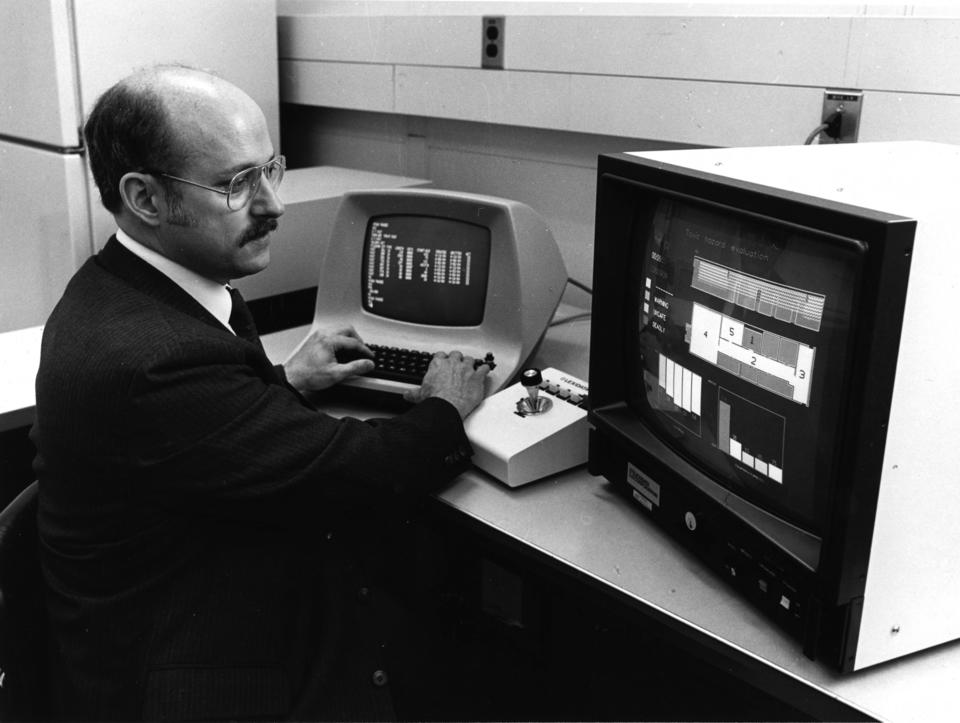

Fire engineer Walter W. Jones working in 1989 on HAZARD I, one of NIST’s first computer programs for simulating fire and smoke behavior in a variety of buildings and structures. NIST continues to advance the science of fire and smoke modeling, providing tools that are used worldwide.

To enhance fire safety aboard Amtrak trains, NIST has studied the burning behavior of materials used for passenger seating since the 1970s. In this 1997 test, a NIST engineer uses an infrared camera to map fire spread.

Recreations of tragic fires, including this 2003 simulation of a burning office in one of the World Trade Center towers after the terrorist attacks on 9/11, have helped NIST researchers recommend changes to building and fire codes that improve occupant safety.

A 2010 NIST burn in a dormitory scheduled for demolition at the University of Arkansas addressed three areas of fire safety in which NIST has been a leader for decades: evaluating smoke and fire detector performance, demonstrating the value of sprinklers, and defining dorm room fire hazards.

Results of NIST burn studies and laboratory tests in 2012 helped prompt a safety alert about heat-caused damage to faceplate lenses used by firefighters. NIST later developed a rigorous test for certifying lenses as resistant to the hazard.

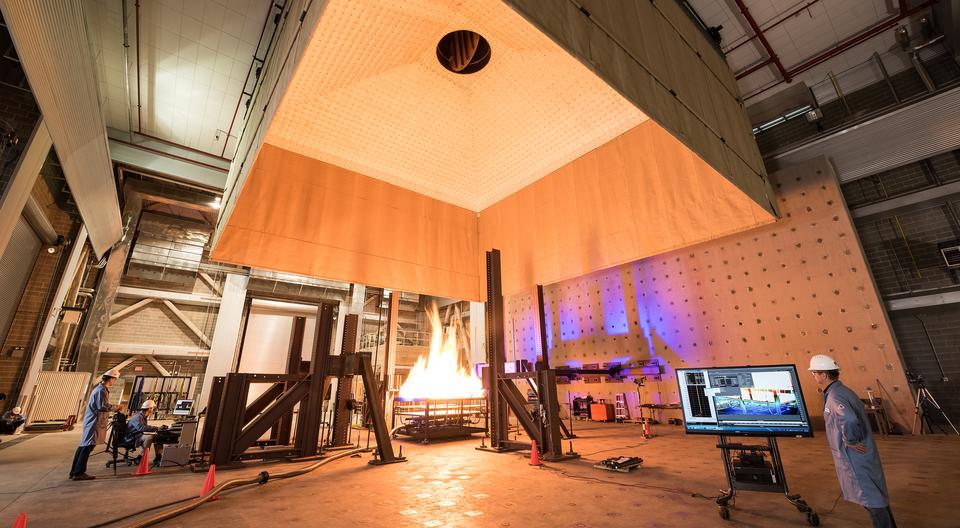

Opened in 2015, NIST’s National Fire Research Laboratory is a unique experimental facility for understanding fire behavior and structural response to fire. NFRL researchers can study entire homes, offices, bridges and other structures up to 9 meters (30 feet) in height, as well as the impact of fire on new construction materials and methods.

In 2017, NIST demonstrated how an overly dry Christmas tree could be consumed by flames in less than a minute, turning a lovely Yuletide setting into a deadly menace.