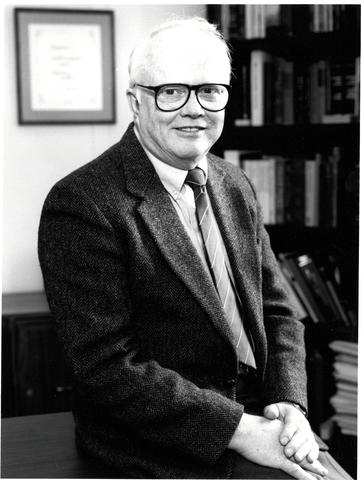

John W. Lyons

John W. Lyons, a chemist who served as director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) from 1990 to 1993 and guided the organization as its mission expanded in support of U.S. industry, died on March 14 in Frederick, Maryland. He was 93 years old.

President George H.W. Bush appointed Lyons to be the ninth director of NIST in 1990. He first came to the agency, then called the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), in 1973, following an 18-year career at the Monsanto Chemical Company, where he became known for his expertise in the chemistry and use of fire retardants. The bureau recruited Lyons to lead its newly formed Center for Fire Research.

1973 marked a pivotal year for fire safety in the U.S. The National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control published a landmark report that year, America Burning, that described the devastating toll of lives lost to fire in the U.S. The report criticized what it called the nation’s indifference to the fire problem and called for a comprehensive effort by government, industry and the public to address it. It was against this backdrop that Lyons took the helm of the bureau’s new Center for Fire Research.

“There had been very little research on fire before this time,” said Jack Snell, a NIST research scientist who would later lead the center himself. The researchers there set out to change that. “We wanted to understand why fires behaved the way they did,” Snell said. “What makes a fire ignite? What causes the flames to spread?”

Researchers at the center probed the fundamentals of fire by studying combustion at the atomic and molecular level. They also conducted practical studies, including methods to test the performance of electronic fire detectors and sprinkler systems. Those performance tests were incorporated into standards that were then written into building codes, radically improving fire safety across the nation.

“We weren’t the only ones working on fire research,” Snell said. “But under John’s leadership, we had a tremendous impact, leading to fundamental changes in the way fire safety is done in the country and around the world.”

According to the National Fire Protection Association, the death rate due to fire in the U.S. dropped by roughly 60% between 1980 and 2022.

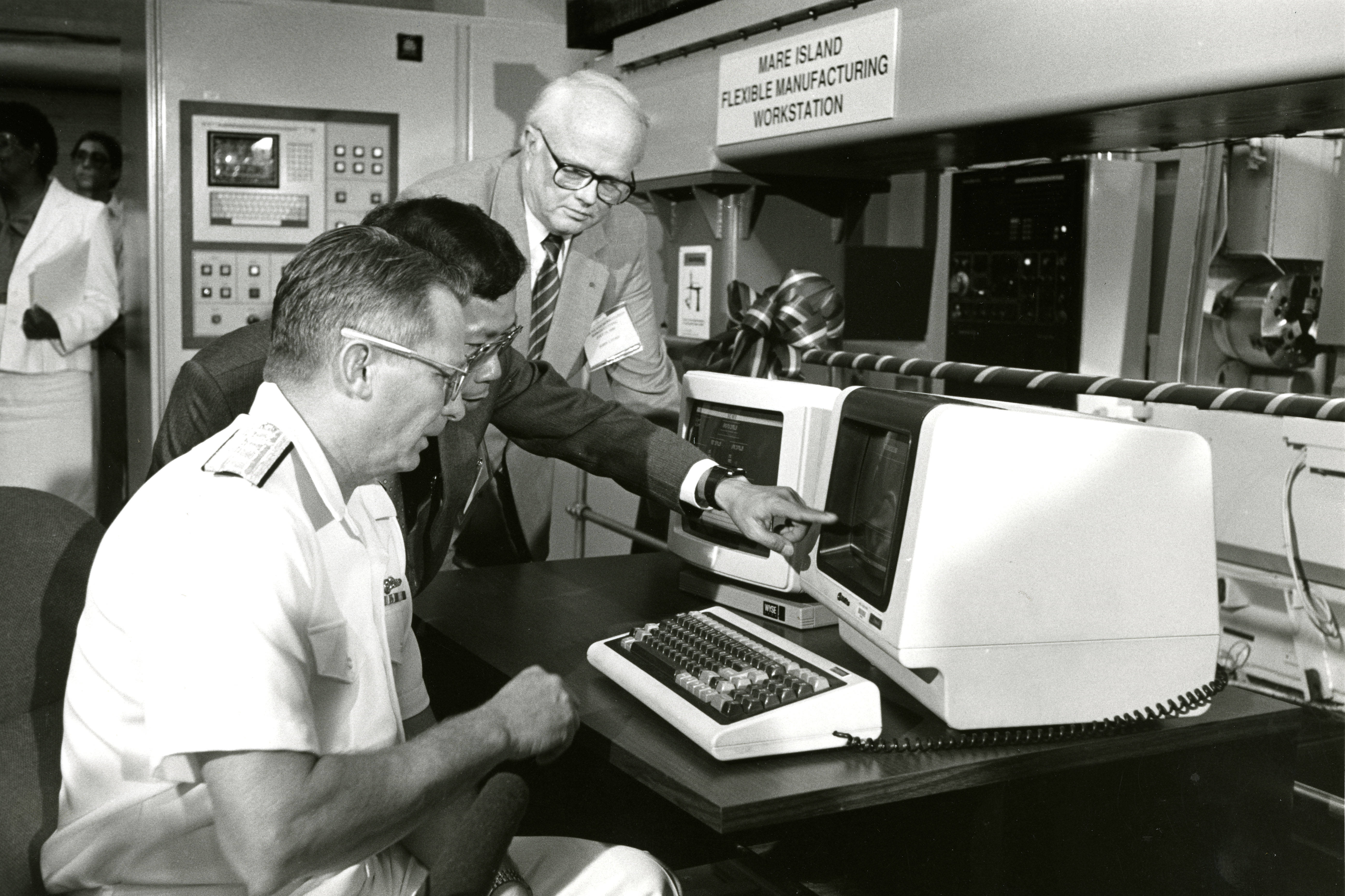

In 1978, Lyons became the first director of NBS’s newly formed National Engineering Laboratory (NEL). Computers and robotics were revolutionizing manufacturing at the time and, under his leadership, the NEL expanded its Automated Manufacturing Research Facility. A test bed and proving ground for these new technologies, the facility hosted industry researchers who then brought new manufacturing methods back to their firms. This proved to be a successful model for technology transfer, and the experience prepared Lyons to lead the bureau through the most significant transformation in its history.

During the 1980s, there was growing alarm that the U.S. was losing its technological edge. Trade deficits were growing as Japanese and other foreign manufacturers prevailed in markets long dominated by the U.S. In response, in 1988, Congress passed the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act, which charged NBS with making U.S. industry more competitive while still maintaining its traditional role in measurement, calibration and standards.

Reflecting on this period during an unpublished interview in 2013, Lyons said, “It did change the nature of the institution because no longer were we simply doing detailed measurement studies in physics and chemistry, but we were now getting into things of interest to industry in the technology areas.” At the same time, Lyons said, “We were still doing the original measurement work and doing it well.”

In recognition of the new emphasis on technology, the act changed the bureau’s name to the National Institute of Standards and Technology. It also created, among other things, the Manufacturing Technology Centers program to accelerate technology transfer to small and medium-sized manufacturers. That eventually became the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program, which still promotes manufacturing innovation across the nation today.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton came into office and appointed a new NIST director. Lyons went on to become director of the U.S. Army Research Laboratory in nearby Adelphi, Maryland, and later served as a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Center for Technology and National Security Policy at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C.

Lyons left NIST more than three decades ago, but there are many parallels between that era and today. NIST is once again being called on to support U.S. industry in the face of global challenges, this time with perhaps even greater urgency. NIST’s new assignments in semiconductor manufacturing and artificial intelligence are transforming the institution once again in potentially lasting ways.

During that 2013 interview, Lyons was asked how he would like to be remembered. “As somebody that could straddle science and technology,” he said, “and who could actually support basic work and at the same time worry about the application or the results of that work.”

By focusing on both sides of that equation, John Lyons steadily guided NIST through a time of great change. As NIST once again navigates a pivotal moment in its history, there is no better time to honor him and to remember his success.

Editor’s Note (6/27/2024): We have updated this article to correct the timing of Jack Snell’s work at the Center for Fire Research. He worked there after John Lyons left the center, not at the same time.