How Metallurgists Saved Apollo Rockets That Languished in the Ocean for Decades

- Rocket pieces from the Apollo missions to the Moon languished on the Atlantic Ocean floor for decades.

- But in 2013, pieces of the rocket engines were retrieved.

- NIST experts helped analyze and preserve some of these pieces, including a thrust chamber, exhaust nozzle and engine blade.

Massive Saturn V rockets launched astronauts into space during the Apollo missions to the Moon in the 1960s and 1970s.

To reach the Moon, individual rocket pieces, known as stages, were discarded as they ran out of fuel. The first stages of the Saturn V rocket fell into the Atlantic Ocean and stayed there for more than 40 years.

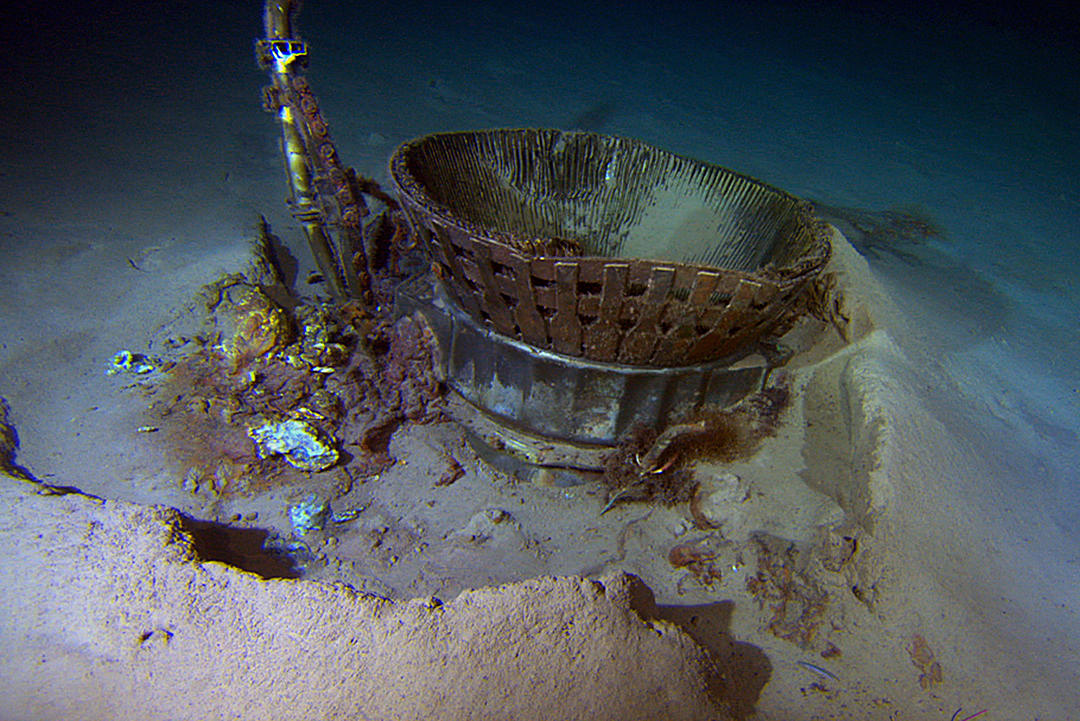

That is, until 2013, when Bezos Expeditions led an effort that recovered 11,300 kilograms (25,000 pounds) of components from the F-1 engines.

The recovered items were taken to the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center in Hutchinson, Kansas, for processing.

Two types of items — thrust chambers and an exhaust nozzle — posed a special problem for conservators. They were constructed of a nickel-based superalloy called Inconel X-750, which was designed to withstand very hot temperatures.

Unfortunately, no one had ever studied the reaction of this material to decades of seawater exposure, so the conservation team did not know how best to treat the artifacts made from it.

The Kansas Cosmosphere staff asked National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) engineers Tim Foecke and Adam Creuziger for help.

They discovered that the superalloy's structure was altered by the very thing it was designed to withstand — the incredibly high heat of the F-1 engine exhaust. The Inconel X-750, which started out composed of microscopic cube-shaped elements, transformed into a substance made up of tiny branch-like structures called dendrites. Luckily, that change made it easier for Foecke and Creuziger to remove corrosive salts left behind by exposure to seawater.

NIST experts also did extensive work to conserve the engine’s turbine blades.

Today, the recovered F-1 engine parts may be seen at:

- the Kansas Cosmosphere

- the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

- the Museum of Flight in Seattle

- the Kent, Washington, headquarters of Blue Origin, the Bezos company developing commercial space vehicles