Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

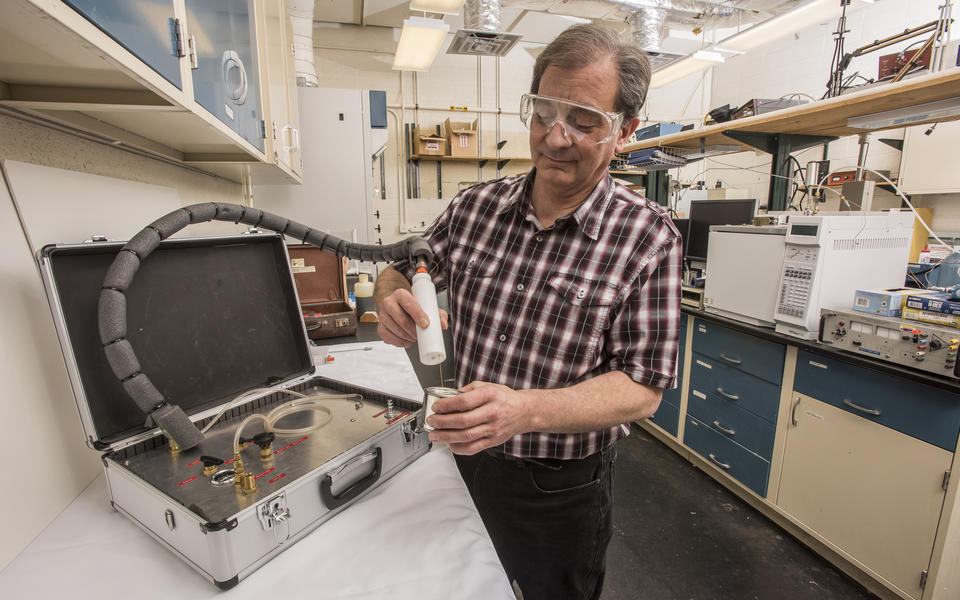

Here I am sampling the vapor inside an old paint can with a portable version of an instrument I invented to recover trace chemicals such as environmental pollutants and forensic evidence. The underlying technique is called PLOT-cryoadsorption, or PLOT-cryo, which is short for porous layer open tubular cryogenic adsorption.

While NIST is not a teaching institution per se, teaching comes naturally to many of us who work here. We’re always describing our work in scientific meetings, so it’s not a giant leap to actually teach courses on what we do, though it’s perhaps a little more challenging to teach people about technical subjects they’re not familiar with. And that’s especially true when your students are judges whose understanding of the power and limits of certain types of forensic evidence can have such a profound effect on the lives of others.

That’s why it’s so important to get things right.

Recently, our research group provided a short course on vapor sampling and characterization for 13 members of the judiciary. Unlike the kinds of presentations we usually give, this short course had all the components of a university-level program, complete with lectures, lab sessions and recitations.

It all started when I patented a field-portable vapor sampling device a few years ago. That development caught the attention of the executive officer of the National Courts and Sciences Institute (NCSI), Dr. Franklin Zweig. Franklin is both a scientist and a lawyer, and the organization he runs, NCSI, is a nonprofit foundation that provides scientific training to the judiciary, enabling judges to better handle scientific evidence. Judges who complete the training are designated as Resource Judges, or upon completion of multiple training modules, Fellows of the Institute. These specially trained judges then mentor other judges on specific scientific topics.

Two state supreme court justices, five state appellate judges and six trial judges participated in the short course at NIST-Boulder. The main topic was called PLOT-cryoadsorption, a NIST-developed vapor characterization technology that can be used in many different areas of interest to the forensic sciences. In our course, we covered the characterization of vapors that could be helpful in identifying cases of arson. The judges heard lectures on various vapor characterization methods, chemical analysis, mixture behavior and measurement uncertainty. The course also featured five laboratory sessions where the judges had the chance to exchange their black robes for white lab coats and do some experimenting of their own with all the techniques.

We called the capstone lab the “six-pack,” but it wasn’t the kind you might enjoy with a neighbor on a Saturday afternoon. Our six-pack contained six samples of fire debris made by burning gasoline, diesel fuel or no accelerant. With their sample chosen by a throw of the dice, the judges had to figure out what, if any, ignitable liquid was used to start the fire.

Finally, the judges participated in the mock hearing, or voir dire, of an expert witness. Special guests Boulder District Attorney Stan Garnett played his usual role of prosecutor, and prominent Boulder environmental lawyer Marcus Martin served as defense counsel. NIST chemist Jason Widegren played the role of an expert scheduled to testify on vapor sampling for an arson case.

While it’s serious business, I’m pleased to say that the judges enjoyed their time with us, and many would have liked to have had a longer course with more lab time! One appellate jurist wrote back to us expressing that he wished he had taken the course before he had presided over an arson appeal a few months ago. There are currently 60 more judges on the waiting list for two offerings of the course in May 2018. And because the course was so successful, these courses have been expanded to three days.

Although the judges have since returned to their respective benches, my team and I will continue to provide follow-up instruction and periodic consultation to them for the next year. For example, I will give the keynote address at the NCSI Forensics Boot Camp at the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., in March 2018.

We learned much from the judges during the two days we spent together. While judges do not have formal scientific training, they are nonetheless responsible for regulating the flow of scientific information at trial. Under the Daubert standard (one of the more common guidelines for the control of scientific information in court), the judge is indeed the gatekeeper. They must make sure the jurors are presented with the relevant facts, but they must also exclude irrelevant clutter and importantly, guard against the presentation of junk science.

The difficulty of this task and the few means they have to discern between good science and bad science in the courtroom were largely unknown to us. How this adds to the weight of the responsibility on the shoulders of these judges can hardly be exaggerated. On the one hand are the victims seeking justice and closure so they can begin to rebuild their lives. On the other hand, there is the potential denial of justice and freedom for the defendant, who may well be innocent. Again, this is why it’s important for judges to have the skills they need to gauge the quality of forensic evidence, especially in an age where so many people regard it as nearly infallible. Nothing is infallible, people make mistakes, but with care and critical thinking we can improve the way forensic evidence is presented and evaluated in court, to the benefit of all.

I’m a bit unique at NIST in that I have served as an expert witness and forensic consultant for the Department of Justice, United States Attorney’s offices, and the FBI. I’d always told my colleagues how rewarding it is to help law enforcement agencies to get at the truth with the proper use of science, so I was delighted when we could involve my entire group in the training of these distinguished jurists. I’m sure that we were all intimidated being in a room with these folks, but we were quickly put at ease by this wonderfully friendly and deeply curious group.

We’re all looking forward to October 2018 and our next two classes!