Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

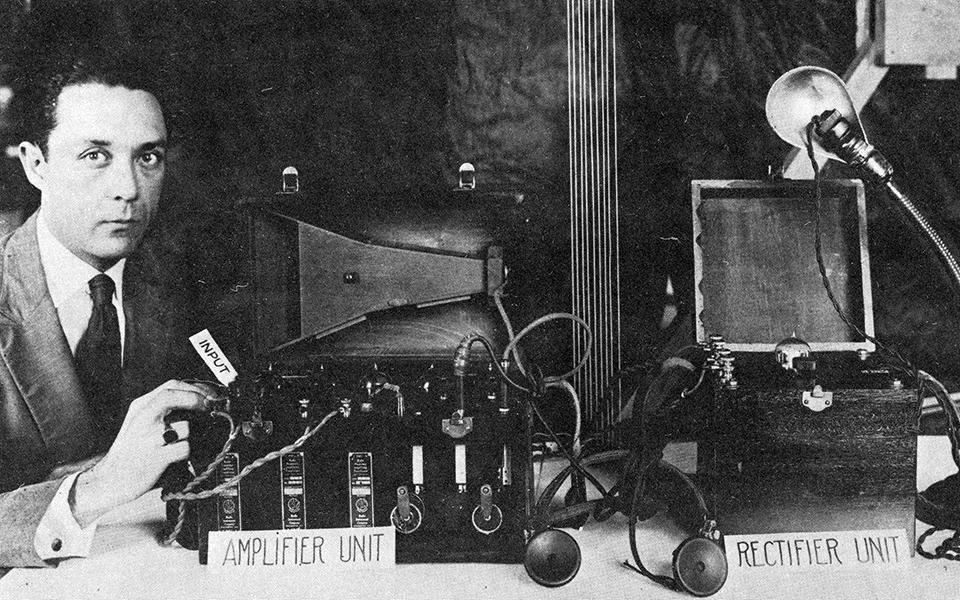

Percival Lowell with his patented radio set powered by alternating current.

Even if you weren’t able to watch the recent Super Bowl on TV, you could still listen to the play-by-play commentary on the radio. But radio does more than just broadcasting sporting events or playing music. It plays a major role in emergency response, navigation and science.

‘Radio’ vs. ‘Wireless’

The word “radio,” however, didn’t become part of our regular vocabulary until 1911, and it happened thanks in part to J. Howard Dellinger, a radio scientist at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), the agency that became the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). This came about when the second International Radiotelegraph Conference was being planned in London, and a professor sent Dellinger a paper that he was going to present to the conference for review.

At the time, “wireless” was used as the term for radio communication, especially by the British. However, NIST was charged with revising standards in preparation for the conference, and Dellinger suggested that the professor use “radio,” which was already becoming a popular word in the U.S., instead of “wireless.” The professor agreed, and the word “radio” went on to become the universally accepted term.

Dellinger not only played a role in popularizing the word “radio,” but he also played a role in the first radio work done at NIST. A commercial company asked NIST to calibrate a wavemeter, a device developed by one of its engineers that measures electromagnetic waves like those of radio. Dellinger was known as the wireless expert and took on the project of calibrating the first radio instrument at NIST.

A New Type of Radio Receiver

But for radio to become mainstream, it first had to be commercialized, which began with its introduction into households. However, the challenge was building a radio set that used the electrical current, called alternating current (AC), which powered lights, fans and kitchen appliances when plugged into wall sockets. The predecessor to this technology was developed and patented by two researchers, Percival D. Lowell and Francis W. Dunmore, at NBS in 1922. They called their invention the “mousetrap.”

The “mousetrap” was a receiver for a radio amplifier that could run on AC. This was considered a breakthrough because at that time radios were only able to be powered by direct current (DC) provided by batteries. These batteries were bulky and heavy, had to be charged from time to time and were considered dangerous because of the acid used in them. The researchers’ prototype meant the radio could be used in homes without causing damage and with the same performance quality.

Lowell and Dunmore filed two more patents together for other innovations, and for the “mousetrap” they sold the rights to the Dubilier Condenser Corporation. Little did they know that, because there was no uniform policy on patents issued to government employees, their actions would result in more than a decade of litigation over who legally had the rights to the patent.

While they were tied up in court, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) developed its own model of the AC radio in 1926. Its model later became the first AC-powered radio sold to consumers.

Flying by Radio

During the early years of flight navigation, NIST was doing research to assist pilots while they were flying and landing. Pilots needed three things to get their bearings when flying “blind,” meaning it’s foggy, too dark or too cloudy to see. They needed to know the longitudinal position, altitude and speed of the aircraft, which were all achieved by various beacons installed in the plane. The remaining issue was that there were two frequencies the pilot constantly had to switch between the frequency that the Department of Commerce used to send weather information to planes and ships, which sometimes caused interference for pilots, and the frequency the radio beacon operated on, which gave altitude and other information.

Dunmore created a prototype, but Harry Diamond, a radio engineer who joined NIST in 1927, completed the device, called the radio guidance system. Diamond solved the problem by developing a separate device that allowed for voice communication to the pilot without receiving any outside interference from ships’ radios.

A Curtiss Fledgling, a trainer aircraft developed for the U.S. Navy, was equipped with the device, and flight tests were performed between NIST's experimental air station at College Park, Maryland, and Newark Airport in New Jersey in foggy weather. After a series of successful tests were performed, the device was turned over to be used by the Department of Commerce in 1933.

Praise From a Famous Inventor

While mostly intended for serious users, some of NIST's journals and publications were popular with the public. One such book, titled The Principles Underlying Radio Communication, covered topics such as elementary electricity, radio circuits and electromagnetic waves and was also published as a textbook for soldiers in the U.S. Army. The famous inventor Thomas Edison received a copy from NIST and wrote a letter thanking the first director, Samuel W. Stratton, for publishing it, saying it was “the greatest book on this subject that I have ever read.”

As these and other examples show, NIST had a significant influence on radio research between 1911 and 1933. However, NIST’s radio work didn’t end with the first blind landing. NIST would continue to contribute to the field leading up to and during World War II, and research continues to this day in areas such as 5G, public safety communications and spectrum sharing.

About the author

Related posts

Comments

Hi, Geoff. You may want to reach out to the National Capitol Radio and TV Museum for assistance. Your local area may also have a radio swap meet that could offer parts and advice.

I have two early pieces of radio apparatus that Lowell and Dunmore made and would like to know where I can get missing parts to fully restore these items.