To Help Protect Our Elections, NIST Offers Specific Cybersecurity Guidelines

Plain-language guide provides strategies to guard election-related technology against cyberattack.

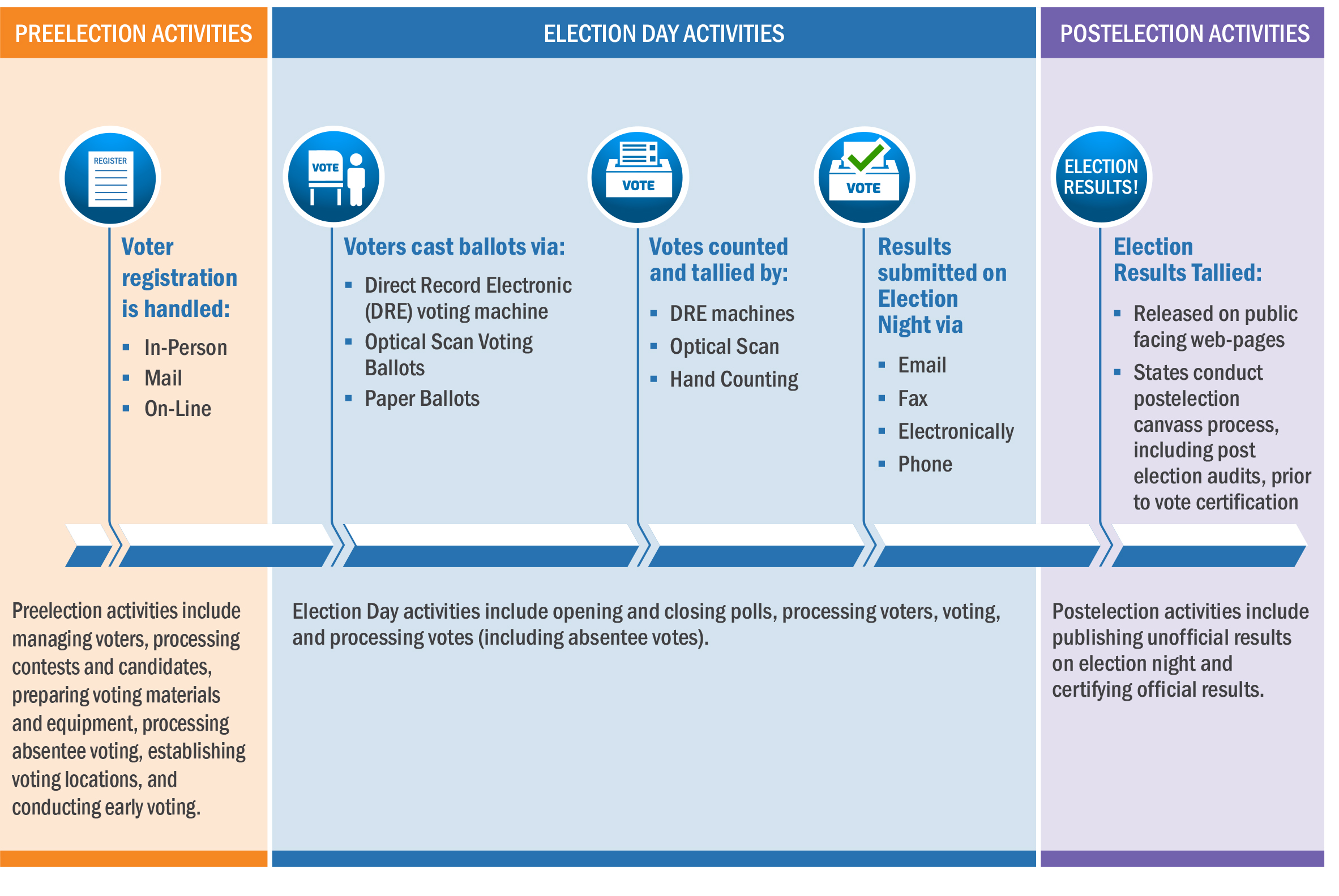

Making elections secure means protecting against ever-evolving threats to information technology — which scans in-person and mail-in ballots, supports voter registration databases and communicates vote tallies.

To reduce the risk of cyberattacks on election systems, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has released draft guidelines that provide a road map to help local election officials prepare for and respond to cyber threats that could affect elections. Comments on the draft will be accepted through May 14, 2021.

Written in everyday language, the Draft Cybersecurity Framework Election Infrastructure Profile (NISTIR 8310) draws upon the experience of election stakeholders and cybersecurity experts from across the country, offering an approach for securing all elements of election technology.

“This is the first time we have looked at the entire election infrastructure and put together a cybersecurity playbook,” said NIST’s Gema Howell, one of the publication’s authors.

The guide applies the principles of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework to election systems. Widely adopted by industry, the framework is not a regulation, but a set of recommended best practices for computer security. NIST has been creating tailored guidance called “profiles” to help particular sectors of society — such as manufacturers — adopt the framework to address their specific needs.

The new guide is a profile tailored to election infrastructure, which includes not only physical locations such as polling places, but also the technology involved in voter registration databases, voting machines and the networks that connect them. Like other parts of the nation’s critical infrastructure, these systems are an attractive target for cyberattacks. Not included in the guide are systems dedicated to social media, and the systems and software dedicated to supporting campaigns and individual political groups are likewise beyond its scope.

There are several thousand voting jurisdictions in the United States. While state and federal governments play roles in elections, such as providing training courses on running the state’s elections and providing a process for testing and certifying voting equipment, most of the nitty-gritty work of running an election happens at the city or county level, with individual polling places staffed largely by volunteers.

The guide can help these officials reduce the risk of disruptions to the major tasks they must perform in the process of an election. These range from the immediate concerns of an election day, such as vote processing or communicating the details of a problem or crisis, to longer-term efforts, like maintaining election and voter registration systems.

Because individual jurisdictions have their own technologies and approaches to running elections, Howell said, the guide is organized in a way that can help with any system.

“We start by helping you think about the election objectives you want to accomplish,” Howell said. “Then we help you think through how to prioritize your cybersecurity needs based on those objectives. Once you’re there, we provide informative resources to mitigate your cybersecurity risks.”

NIST developed the profile in collaboration with experts from government and industry. Through the Help America Vote Act of 2002, NIST is charged with helping to improve U.S. election systems by focusing on technical aspects of voting and related activities.

The authors worked with state election officials, the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (DHS CISA), the DHS Election Infrastructure CSF Joint Working Group, and technology developers including voting system manufacturers.

To submit comments on the draft, please email them to NISTIR-8310-comments [at] nist.gov (NISTIR-8310-comments[at]nist[dot]gov).