SOCIAL SPOTLIGHT: GEORGE QUINN AND ROMAN GLASS FRACTOGRAPHY

Cracking the code for artifacts of antiquity — NIST guest researcher George Quinn is applying his expertise in fractography to ancient Roman glass.

Our world is built on ceramics and glass, from colorful windows decorating our finest architecture to parts for engines and bullet-resistant windshields. This is George’s realm, where he uses precise measurement techniques to interpret what makes these materials fracture.

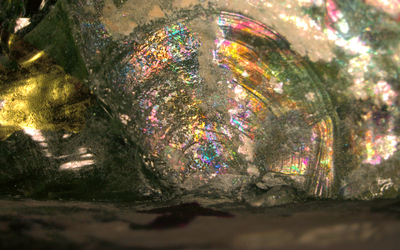

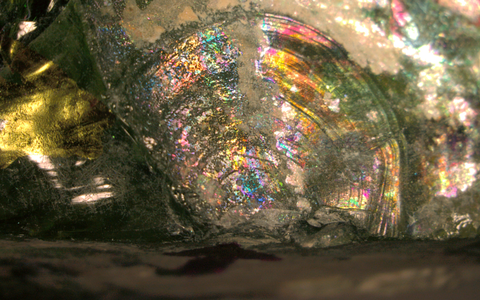

But what about glass from the days of old? Centuries ago, ancient Romans discovered an incredibly stable form of glass (soda lime silica) and traded it throughout their empire. Some remnants now rest in the Corning Museum of Glass, which maintains finished and raw fragments unearthed in Israel at an archaeological dig in the 1960s.

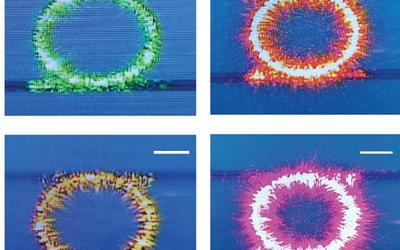

Since the pieces’ chemical compositions are nearly identical to modern glass, museum researchers connected with George to investigate some raw samples. He and colleague Jeffrey Swab from the U.S. Army Aberdeen Proving Ground cut bars from the glass chunks, then introduced a controlled crack about one-third to one-half of the way through them and finally bent them until they broke into two pieces.

As it turns out, Roman glass is pretty close to modern glass, just 6% less resistant to fracture.

In an archaeologist’s toolbox, modern fracture analyses like this can help us learn how ancient glass was made or how it broke. In this case, the lower resistance could be from degradation while buried for centuries or a hasty process that Romans may have used to make the raw stock quality glass.

Our NISTers are incorporating the findings into the next edition of Fractography of Ceramics and Glasses, a widely used practice guide for the ceramic and glass industry. In the meantime, you can find more details about this research in the Journal of Glass Studies.

Follow us on social media for more like this from all across NIST!