The Criteria Framework and Award Process Are Born

The law required “guidelines and criteria that can be used by business, industrial, governmental, and other organizations in evaluating their own quality improvement efforts; and....... specific guidance for other American organizations that wish to learn how to manage for high quality by making available detailed information on how winning organizations were able to change their cultures and achieve eminence.” That summer, Reimann began developing those “guidelines and criteria,” starting with a framework, now called the Criteria for Performance Excellence®.

Reimann said he sought to design an enduring knowledge structure to move quality away from a “guru focus” common in the quality community at that time. “My conviction was that we had to create a nonprescriptive framework for defining and assessing, which was not tied to any gurus but would still allow companies that were influenced by such gurus to respond [with their own best practices]....... We saw our main NBS purpose as sharing knowledge and lessons learned. We were very concerned that a guru orientation might undermine this central purpose and perhaps also split the communities at the very time we needed broadly based cooperation.

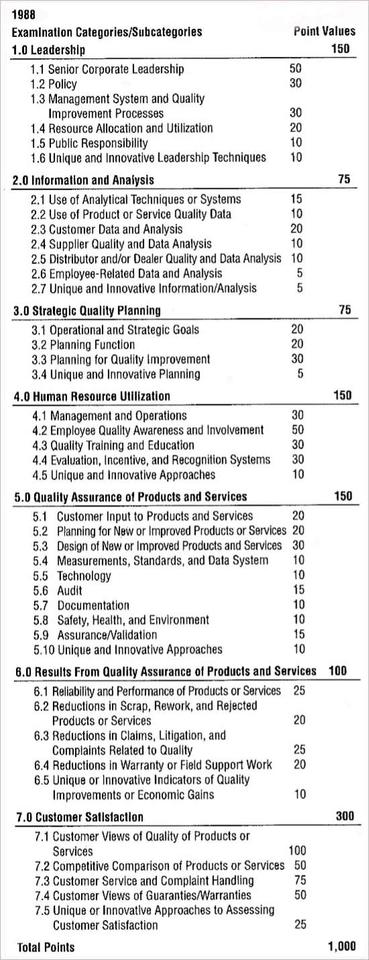

The idea of a nonprescriptive approach was simply in NBS’s genes, Reimann said. He worked alone in the summer of 1987 to create the knowledge structure: leadership, strategic quality planning, information management, human resources, and process management. These terms have evolved over the years, but, Reimann said, they were his synthesis of the components necessary to distinguish overall quality management from narrower quality control and productivity requirements.

Coursey noted that the legislation was not specific about the working parts of the program—the Board of Examiners, the judges, the Foundation—and Reimann had to figure out how these groups would be structured. After a few weeks, Reimann and Coursey visited Jim Turner of the House committee staff where Reimann discussed ideas about roles and responsibilities for these different groups. Since there was to be no government funding, a mechanism was needed to raise and administer private‐sector funding to pay operational expenses for the award program. It was determined that this funding would come from a foundation, and, although NBS had some legislative responsibilities for oversight of the program, day‐to‐day award operations were to be run by a private‐sector entity under contract to NBS. While Reimann worked on the criteria, award organization, and recruitment, Coursey went to Washington, DC, to finalize the mandatory legal instruments called out in the public law: the Panel of Judges and Board of Overseers. Reimann said Coursey’s work was very important, demanding, and sometimes tedious.

The overall award design integrated award processes with a team structure. This required a large board of examiners, with a smaller number of senior examiners who would lead consensus and on‐site reviews. Reimann said he wanted a sharp separation between judging and scoring because he did not believe that a scoring process alone could provide balance of judgment on the applicant companies, including the importance and success of their quality efforts, and the degree to which they could serve as U.S. role models. He felt this judgment should be determined in deliberation by a Panel of Judges after the panel had all the background facts available: scoring and a site visit report on strengths and weaknesses. The Panel of Judges had the additional challenge in that the law limited the Baldrige Award to no more than two winners in each of three categories.

Reimann said that in creating the multi‐ examiner, multi‐stage assessment, he was strongly influenced by his NBS background in measurement variability. “We wanted to ensure independent scoring, consensus scoring, and an opportunity to examine the highest‐scoring contenders via site visits. At that point, the scoring would be a smaller factor because the judges needed to make their final recommendations in a balanced way,” he said.

Another element of the first criteria was explicit recognition of the distinction between technical quality and quality management. In this regard, focusing on the customer factors rather than the mainly technical ones was critical. In his book, Managing Customer Value, marketing expert Bradley Gale wrote about an NBS meeting in December 1987 to review the newly created criteria,

In 1987, quality advocates were divided into factions supporting competing gurus....... And, unfortunately, companies could achieve quality as any of the gurus defined it, yet still fail to produce a product that would win and keep customers....... Quality experts were....... eager to advocate that the award committee require mathematical tests to measure whether mathematical processes were “in control.” But as for measuring customer satisfaction relative to competitors, they were either uninformed or downright skeptical of the idea that anyone could provide statistical evidence to identify which companies were truly creating happy customers.16

Reimann said that customer‐driven quality needed to be a key driver for technical quality. In an interview in 1998, Reimann elaborated on the customer focus of the criteria requirements, “We knew that we couldn’t make the award a ‘techie’s paradise’ with quality viewed primarily as parts per million defects. The issue is customer and market satisfaction. We needed to recognize companies that show clear connections to customer satisfaction and market share through their defect and error‐reduction processes.”17

Reimann added that the Criteria for Performance Excellence® were expected to be in a “state of evolution,” refined to keep up with the validated management practices of the time. “We aggressively pursued improvement of the criteria from the start.”18

16 Gale, Bradley, Managing Customer Value: Creating Quality & Service that Customers Can See, New York: The Free Press, 1994

17 Bell, Robert and Keys, Bernard, “A Conversation with Curt W. Reimann on the Background and Future of the Baldrige Award,” Organizational Dynamics, American Management Association, Spring 1998

18 Bell, Robert and Keys, Bernard, “A Conversation with Curt W. Reimann on the Background and Future of the Baldrige Award,” Organizational Dynamics, American Management Association, Spring 1998

Contacts

-

Baldrige Customer Service(301) 975-2036NIST/BPEP

100 Bureau Drive, M/S 1020

Gaithersburg, MD 20899-1020