Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

My Stay-at-Home Lab Shows How Face Coverings Can Slow the Spread of Disease

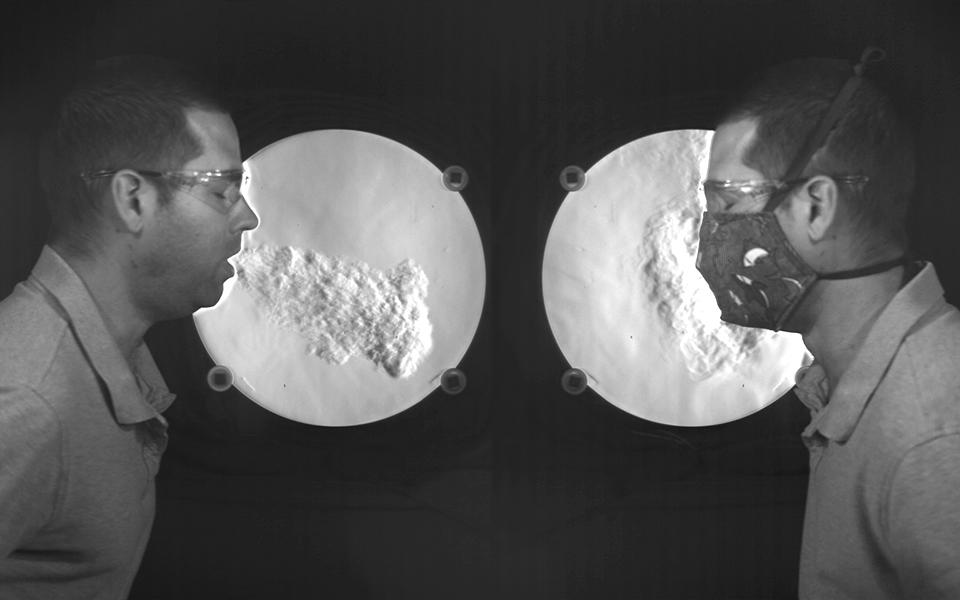

Note: This high-speed visualization illustrates airflow when coughing, IT DOES NOT show the movement of virus particles. As you can see, the uncovered cough expels a jet of air, whereas the covered cough stays closer to my face.

As a fluid dynamicist and mechanical engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), I’ve devoted much of my career to helping others see things that are often difficult to detect. I’ve shown the complex flow of air that occurs when a dog sniffs. I’ve helped develop ways to detect drugs and explosives by heating them into a vapor. I’ve explored how drug residue can contaminate crime labs. I’ve even shown how to screen shoes for explosives.

Most of these examples fit into a common theme: detecting drugs and explosives through the flow of fluids that are usually invisible. When I’m in the laboratory, I use a number of advanced fluid flow visualization tools to help better understand and improve our ability to detect illicit drugs and explosives on surfaces, on people and in the environment.

When COVID-19 emerged as a threat to our global community, I pondered how I could use these unique visualization tools to help. These measurement systems excel at showing how air moves around, so it was clear to me that I could use these tools to create qualitative video content that illustrates the importance of wearing a face covering and the pros and cons of various kinds of homemade face coverings in an easily understandable way.

Building the lab

I was allowed to bring parts of my scientific flow visualization equipment home with me during the quarantine. I have a fairly elaborate woodshop in my home (woodworking is an addiction — I mean, hobby — of mine), and this is where I set up my flow visualization gear for these experiments.

Schlieren imaging is one of the primary tools I use for airflow visualization experiments, and is a true workhorse in my NIST lab, drawing a lot of attention during VIP tours because of the striking visuals it provides. The schlieren technique allows us to see changes in temperature in air. So, if you place your hand in the test section, you will see the warm air rising from your hand. If you ignite a lighter in the test section, you will see a strong buoyant plume of hot air rising from the small flame. And if you put your face in the test section and cough — you guessed it — you will see the warm air exit your lungs and shoot out of your mouth and nose as an air jet.

Our schlieren system is a sophisticated optical device, utilizing several lenses, optical components and a 45.72 centimeter (18-inch) first-surface concave spherical mirror. These systems can be finicky to assemble and align and almost always require large, heavy laser tables for vibration stability, ease of alignment and structural rigidity. Obviously, I couldn’t bring my 725.74-kilogram (1,600-pound) laser table home with me, so I tried something I’d never done before — build a schlieren system with tripods and wood. After a few days of construction and alignment, it worked! Check out this time-lapse video of my shop being transformed into a home laboratory!

Testing the coverings

With a fully functional schlieren optical system, a high-speed camera and a six-second commute from home to my “lab,” I was ready to begin collecting data on the qualitative effectiveness of various homemade face coverings. Gail Porter (director of the NIST Public Affairs Office), Jennifer Barrick (NIST Public Affairs Office) and Amy Engelbrecht-Wiggans (NIST Material Measurement Laboratory) provided all the homemade face coverings for this effort. Gail and I would talk often and narrow down the best features of certain face-covering designs, and then she would create new coverings and drop them off on my back deck. I’m actually pretty good with a sewing machine, but Gail’s and Amy’s skills are off the charts. I looked at 26 different face coverings, each with a different geometry, fabric or material combination, and tying mechanism. Leon Gerskovic (NIST Public Affairs Office) was my cinematography mentor and guided me through the entire effort.

After weeks of data collection, over 50 GB of video data (looking at yourself coughing over and over gets a little strange after a while), and literally hundreds of fake coughs, we had a clear message — “cover smart, do your part, slow the spread.” We learned that even the simplest face coverings (bandanas, ski neck warmers, etc.) stopped much of your cough from landing on someone else. We also learned that a good seal around the nose, chin and cheeks helps to prevent your cough from “leaking” out of the covering. And pulling your face covering below your nose is not good — you would be surprised how much air comes out of your nose when you cough.

Additionally, we found that fabrics with very tight and nonporous weaves actually increase air leaking out by the nose and chin. So, while these tight fabrics may filter droplets at a greater efficiency, they are not breathable and could possibly defeat the purpose of the face covering. Another interesting observation was the impressive reduction in airflow velocity while talking with all the face coverings — a good thing considering that most people out in public should be talking far more than coughing.

My hope is that the video content that was generated by these efforts provides a helpful illustration for why we all should cover up in public spaces and while near others. The good news is that even the most basic face coverings qualitatively appear to reduce the distance the air exiting your lungs during talking and coughing travels. The bad news is that many people will be watching a video of me coughing over and over again — mildly embarrassing, but I’m getting used to it. I have some plans to continue visualizing face coverings using mannequins and fog droplets, so stay tuned!

How Can NIST Help: Collaborating at a Distance to Defeat COVID-19

Check out this post by Heather Evans about NIST's other efforts to help fight the coronavirus.

About the author

Related Posts

Comments

Face coverings, such as masks and face shields, have been shown to slow the spread of disease by reducing the amount of respiratory droplets that are released into the air when an infected person speaks, coughs, or sneezes.

A simple experiment that can be performed at home is to demonstrate the effect of face coverings on the spread of respiratory droplets. This can be done by using a spray bottle to simulate respiratory droplets and a laser pointer to track the movement of the droplets.

By speaking, coughing or sneezing into the air, without a mask and then repeating the process with a mask on, you will be able to see the difference in the number of droplets released. This will clearly demonstrate how face coverings can slow the spread of disease by reducing the amount of respiratory droplets that are released into the air.

It's important to note that this is a simplified experiment to demonstrate the basic principle of face coverings, but it's not a substitute for professional or scientific studies.

In the midst of a global pandemic, understanding the efficacy of face coverings in slowing the spread of disease has become crucial. As individuals around the world adapt to new safety measures, a stay-at-home lab experiment can provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of face coverings. By conducting a simple experiment, we can observe firsthand how face coverings can help in reducing the transmission of respiratory droplets and potentially curb the spread of infectious diseases.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread, the importance of face coverings in slowing the spread of disease has become increasingly clear. My stay-at-home lab experiments have demonstrated the effectiveness of face coverings in reducing the transmission of respiratory droplets, the primary means by which the virus spreads.

In my experiments, I used a fan to simulate respiratory exhalations and a laser to visualize the droplets produced. I then repeated the experiment with a face covering and observed a significant reduction in the number and size of droplets released. This demonstrates that face coverings can effectively trap respiratory droplets, reducing the amount that can spread to others.