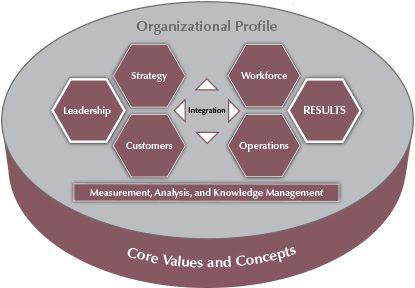

Baldrige Criteria Commentary (Education)

Baldrige Education Criteria for Performance Excellence® Categories and Items

The “why” behind the Criteria, as well as examples and guidance to supplement the notes that follow each Criteria item in the Baldrige Excellence Framework® (Education) booklet.

Explore Free Content | Purchase the Framework

Organizational Profile

Your Organizational Profile provides a framework for understanding your organization. It gives you critical insight into the key internal and external factors that shape your operating environment. These factors, such as your organization’s vision, culture, values, mission, core competencies, competitive environment, strategic challenges, threats, advantages, and opportunities affect the way your organization is run and the decisions you make. As such, the Organizational Profile helps you better understand the context in which you operate; the key requirements for current and future organizational success; and the needs, opportunities, and constraints placed on your management systems.

P.1 Organizational Description

Purpose

This item addresses the key characteristics and relationships that shape your organizational environment. The aim is to set the context for your organization.

Commentary

Understand your organization. The use of such terms as vision, values, culture, mission, and core competencies varies depending on the organization, but these terms should offer you a clear understanding of the essence of your organization, why it exists, and where your senior leaders and/or board want to take it in the future. This clarity enables you to make and implement strategic decisions affecting your organization’s future.

Some organizations define a mission and a purpose, and some use the terms interchangeably. The role of purpose is to inspire the organization and guide its setting of values. Purpose might include making a difference for your students, other customers, stakeholders, and community as part of societal well-being. Your purpose should be translatable into action and incorporated into organizational strategy, goals, and metrics.

Understand your core competencies. A clear identification and thorough understanding of your organization’s core competencies are central to success now and in the future, as well as to competitive performance. Executing your core competencies well is frequently a marketplace differentiator. Keeping your core competencies current with your strategic directions can provide a strategic advantage, and protecting intellectual property contained in your core competencies can support your organization’s future success. Along with performance and financial health, core competencies should be assessed to determine their alignment with your strategic objectives and action plans.

Understand your regulatory environment. The regulatory environment in which you operate places requirements on your organization and affects how you run it. Understanding this environment is key to making effective operational and strategic decisions. Furthermore, it allows you to identify whether you are merely complying with the minimum requirements of applicable laws, regulations, and standards of practice or exceeding them, a hallmark of leading organizations and a potential source of competitive advantage.

Identify governance roles and relationships. Role-model education organizations—whether they are publicly or privately held, or are government or nonprofit organizations—have well‐defined governance systems with clear reporting relationships. It is important to clearly identify which functions are performed by your senior leaders and, as applicable, by your governance board and parent organization. Board independence and accountability are frequently key considerations in the governance structure and for regulatory agencies.

Understand your students’ and your other customers’ requirements and expectations. The requirements and expectations of your student and other customer groups and your market segments might include special accommodation; customized curricula; safety; security, including cybersecurity; reduced class size; instructor qualifications; multilingual services; customized degree requirements; student advising; dropout recovery programs; administrative cost reductions; and distance learning. The requirements of your stakeholder groups might include socially responsible behavior and community service. Role-model organizations have a process to determine the unique requirements of their students and other customers.

Education organizations need to understand student and other consumer and market shifts in requirements and expectations. In addition, student, other customer, stakeholder, and operational requirements and expectations will drive your organization’s sensitivity to the risk of service, support, and supply-network interruptions, including those due to natural disasters and other emergencies.

Understand your ecosystem. With the increase in multidisciplinary services, many education organizations rely ever more heavily on an organizational ecosystem—an interconnected network of suppliers, partners, collaborators, and even customers and competitors, with these roles shifting as necessary. Taking advantage of these ecosystems enables distributed risk management and may result in new organizational models, new students, new talent pools, and much greater efficiency in meeting student expectations. In some cases, the organization’s growth may depend on the collective growth of the ecosystem and its ability to prepare for the future. Ecosystem steps for organizations to consider include reconnecting with partners, maximizing learning through shared information, rethinking offerings in a larger context, using concepts from ecosystem organizations as idea generators, and building nontraditional partnerships.

Understand the role of suppliers. In most organizations, suppliers play critical roles in processes that are important to running the organization and to maintaining or achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. These critical roles are sensitive to limitations and disruptions, especially those due to natural disasters and other emergencies, so they should be considered in strategy and risk management approaches. Supply-network requirements might include on-time or just-in-time delivery, flexibility, variable staffing, research and design capability, process and service innovation, and customized services.

Understand your business model and key revenue drivers. The relative importance of your services, including their percentage of your revenue/budget, and how your organization differentiates itself from competitors, is critical to knowing how you are performing. Similarly, understanding your business model within the context of the education sector is critical for strategic planning and assessment. Your business model and key revenue drivers will be impacted directly by the role of competition, what makes your organization unique, what makes it profitable, the rate of change in the education sector, reasons other organizations are succeeding/failing, education standards, and other factors.

P.2 Organizational Situation

Purpose

This item asks about the competitive environment in which your organization operates, including your key strategic challenges, threats, advantages, and opportunities. It also asks how you approach performance improvement and learning. The aim is to help you understand your key organizational challenges and your system for establishing and preserving your competitive advantage.

Commentary

Know your competitors. Understanding who your competitors are, how many you have, and their key characteristics is essential for determining your competitive advantage in the education sector and marketplace. Leading organizations have an in‐depth understanding of their current competitive environment, including key changes taking place.

Sources of comparative and competitive data might include education publications; national, state, and local reports; conferences; local networks; and education associations. Another source might be third-party surveys or benchmarking activities, including those using national or state norms, local or regional benchmarking consortia, or a national or international group working to ensure the availability of longitudinal data systems that report high-quality data at the individual student level.

Consider strategic challenges, threats, advantages, and opportunities. Operating in today’s highly competitive environment means facing challenges and threats that can affect your ability to sustain performance and maintain your competitive position. Understanding your advantages and opportunities is as important as understanding your challenges and threats. Strategic advantages are the sources of competitive advantage to capitalize on and grow while you continue to address key challenges. Strategic challenges and advantages might relate to technology, programs/services, finances, operations, organizational structure and culture, your parent organization’s capabilities, student and other customers, markets, brand recognition and reputation, the education sector, globalization, your value network, inclusivity, and people.

Know your strategic challenges. These challenges might include the following:

- Changing demographics and competition

- An expanding, decreasing, or changing student population

- Diminishing student retention, persistence, or completion

- Your operational costs

- A decreasing local and state tax base or educational appropriation

- The introduction of new or substitute programs or services

- Rapid technological changes

- The availability of a skilled workforce (i.e., faculty and staff)

- The retirement of an aging workforce

- Turnover in senior leadership

- Economic conditions

- Data and information security, including cybersecurity

- New competitors entering the market

- State and federal mandates

- Merger or acquisition by a new parent organization

Know your strategic advantages. These advantages might include the following:

- Reputation for educational program and service quality

- Leadership in education innovation

- Recognition for services to students

- Image or brand recognition

- Agility

- Digital leadership and technology integration

- Reputation for quality

- Environmental (“green”) stewardship

- Societal contributions and community involvement

Prepare for disruptive technologies. A particularly significant challenge is being prepared for a disruptive technology that threatens your competitive position or your marketplace. Recently, such technologies have included smart phones challenging traditional forms of communication, computing, and commerce of all types; virtual programs and services challenging in-person learning and support; email, messaging, and social media challenging all other means of communication; and app-based services challenging traditional services. Today, education organizations need to be scanning the environment inside and outside the education sector to detect such challenges at the earliest possible point in time.

Emerging technologies that continue to drive change in many industries are the use of data analytics, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, the adoption of cloud operations, large dataset-enabled business and process modeling, enhanced automation, and other “smart” technologies. Three growing uses of artificial intelligence are the following: (1) process automation, including automation of physical and digital tasks; (2) cognitive insight, to detect patterns in vast volumes of data and interpret their meaning (e.g., to understand how students learn and in which areas they are struggling); and (3) cognitive engagement, to enhance student learning through virtual reality and game-based curricula, and to engage faculty, staff, and customers using natural language chatbots, intelligent agents, and machine learning.

Organizations need to be aware of the potential for these technologies to create challenges and opportunities in their own marketplace. While some of these tools may not affect your organization immediately, they will likely affect your competitive environment and result in new competitors for your student base.

Implement an overall system for performance improvement. Your system for performance improvement should include processes to learn and integrate improvements into the next process cycle. Approaches that are compatible with the overarching systems approach provided by the Baldrige framework might include implementing a Lean Enterprise System; applying Six Sigma methodology, including Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DMAIC); using Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) or Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology; or employing other improvement tools.

Leadership (Category 1)

This category asks how senior leaders’ personal actions and your governance system guide and sustain your organization.

1.1 Senior Leadership

Purpose

This item asks about the key aspects of your senior leaders’ responsibilities, with the aim of creating an organization that is successful now and in the future.

Commentary

The role of senior leaders. Senior leaders play a central role in setting values and directions; creating and reinforcing an organizational culture that values and fosters student, other customer, and workforce engagement; fostering a culture of safety, diversity, equity, and inclusion; communicating; creating and balancing value for all stakeholders; and creating an organizational focus on action. Leadership success requires a systematic approach and a strong orientation to the future; an understanding that risk is a part of planning and conducting operations; a commitment to improvement, innovation, and intelligent risk taking; and a focus on organizational sustainability. Increasingly, this requires creating an environment for empowerment, resilience, change, and learning. Today’s environment does not tolerate indecisiveness or delay; therefore, remaining agile is increasingly important for senior leaders.

Role‐model senior leaders. In highly respected organizations, senior leaders are committed to establishing a culture of customer and workforce engagement, developing the organization’s future leaders, and recognizing and rewarding contributions by faculty and staff. They personally engage with students and other key customers. Senior leaders enhance their personal leadership skills. They participate in organizational learning, the development of future leaders, succession planning, and recognition opportunities and events that celebrate faculty and staff. They value diversity and promote equity (fair treatment) and inclusion (intentional engagement) for all people associated with the organization, creating a sense of belonging. Development of future leaders might include personal mentoring, coaching, or participation in leadership development courses. Role-model leaders recognize the need for change when warranted and then lead the effort through to fruition. They demonstrate authenticity, admit to missteps, and demonstrate accountability for the organization’s actions.

Legal and ethical behavior. In modeling ethical behavior, leaders must often balance the demand for delivery of short-term results with setting the expectation for an ethical climate and a policy of integrity first.

Communication. Senior leaders must integrate communication with faculty and staff, students, and other customers that supports two-way dialogue, motivates high performance, and conveys the need for organizational changes.

Creation of an environment for innovation. Leading for innovation starts by setting a clear direction and establishing a supportive culture. Leaders need to communicate about the problems or opportunities the organization is trying to address, and then create a supportive environment and clear process that will encourage and approve intelligent risk taking.

1.2 Governance and Societal Contributions

Purpose

This item asks about key aspects of your governance system, including the improvement of leaders and the governance system itself. It also asks how the organization ensures that everyone in the organization behaves legally and ethically, how it fulfills its societal contributions, and how it supports its key communities.

Commentary

Organizational governance. Organizations need a responsible, informed, transparent, and accountable governance or advisory body that can protect the interests of key stakeholders. This body should have independence in review and audit functions, as well as a function that monitors organizational and senior leaders’ performance.

Legal compliance, ethics, and risks. An integral part of performance management and performance improvement is proactively addressing (1) the need for ethical behavior; (2) all legal, regulatory, and accreditation requirements; and (3) risk factors. Ensuring high performance in these areas requires establishing appropriate measures or indicators that senior leaders track. Role‐model organizations look for opportunities to excel in areas of legal and ethical behavior.

Role‐model organizations also recognize the need to accept risk, identify appropriate levels of risk for the organization, and make and communicate policy decisions on risk. Proactively preparing for risks from adverse societal impacts and concerns may include conserving natural resources and using effective supply-network management processes, as appropriate.

Public concerns. You should be sensitive to issues of public concern, whether or not these issues are currently embodied in laws and regulations. Public concerns that nonprofit organizations should anticipate might include the cost of programs and operations, timely and equitable access to offerings, perceptions about stewardship of resources, student debt, placement/employment of graduates, and shareholders' interests.

Conservation of natural resources. Conservation might be achieved through the use of “green” technologies, reduction of your carbon footprint, replacement of hazardous chemicals with water‐based chemicals, energy conservation, use of cleaner energy sources, or recycling of by‐products or wastes.

Societal contributions. As the concept of corporate social responsibility has become accepted, high-performing organizations see contributing to society as more than something they must do. Identifying key communities and assessing need is the first step in supporting societal contributions. Going above and beyond responsibilities in contributing to society can be a driver of student, other customer, and workforce engagement and a market differentiator; customer and stakeholder value is increasingly being driven by issues such as the environment, societal issues, and safety. Societal contributions therefore imply going beyond a compliance orientation.

Opportunities to contribute to the well-being of environmental, social, and economic systems and opportunities to support key communities are available to organizations of all sizes. The level and breadth of these contributions will depend on the size of your organization, the needs of your community, and your ability to contribute. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG) are a potential source of ideas for an organization to focus its societal well-being efforts.

Community support. Examples of organizational community involvement include

- partnering with businesses and other community-based organizations to improve adult learning opportunities for the workforce or community;

- partnering with organizations in the community to provide or facilitate access to vital services, such as broadband;

- efforts by the organization, senior leaders, and faculty and staff to strengthen and/or improve community services, the environment, athletic associations, and professional associations; and

- giving students and workforce members the opportunity to provide community service.

Based on the Baldrige Excellence Framework®, the Communities of Excellence Framework is a resource for your community support efforts. The framework includes a set of key questions for improving the performance of communities and the people who lead and live in them. Rather than prescribe how communities should structure their leadership, shared initiatives, or action plans, or what their mission, goals, or measures should be, the framework helps communities make those decisions with input from all key sectors and voices.

Strategy (Category 2)

This category asks how you develop strategic objectives and action plans, implement them, change them if circumstances require, and measure progress.

The category stresses that your organization’s long‐term organizational success and competitive environment are key strategic issues that need to be integral parts of your overall planning. Making decisions about your organization’s core competencies and outsourcing decisions is an integral part of ensuring your organization’s success now and in the future, and these decisions are therefore key strategic decisions.

While many organizations are increasingly adept at strategic planning, the organizational agility to rapidly change strategy, operations, and plans as opportunities or needs arise is still a significant challenge. This is especially true given market demands to be prepared for unexpected change, such as volatile economic conditions, national and global emergencies, disruptive technologies, and disruptive events that can upset an otherwise fast‐paced but more predictable marketplace. This category highlights the need to focus not only on developing your plans, but also on your capability to execute them.

The Baldrige framework emphasizes three key aspects of organizational excellence that are important to strategic planning:

- Student-centered excellence is a strategic view of excellence. The focus is on the drivers of student learning, student and other customer engagement, new markets, and market share—key factors in competitiveness and long-term organizational success.

- Operational performance improvement and innovation contribute to short‐ and longer‐term productivity growth and cost containment. Building operational capability—including speed, responsiveness, and flexibility—is an investment in strengthening your organizational fitness.

- Organizational learning and learning by workforce members are necessary strategic considerations in today’s fast‐paced environment. The Education Criteria emphasize that improvement and learning need to be embedded in work processes. The special role of strategic planning is to align work systems and learning initiatives with your organization’s strategic directions, thereby ensuring that improvement and learning prepare you for and reinforce organizational priorities.

This category asks how you

- consider key elements of risk in your strategic planning process, including strategic challenges and advantages, the potential need for change in organizational structure or culture, innovations and technological changes that may affect your organization, potential supply limitations or disruptions, and the potential for changes and disruptions in your environment;

- optimize the use of resources, ensure the availability of a skilled workforce, and bridge short‐ and longer‐term requirements that may entail capital expenditures, technology development or acquisition, supplier development, and new partnerships or collaborations; and

- ensure that implementation will be effective—that there are mechanisms to communicate requirements and achieve alignment on three levels: (1) the organizational and senior leader level; (2) the key work system and work process level; and (3) the work unit, department, school/college, classroom, and individual job level.

The questions in this category encourage strategic thinking and acting in order to develop a basis for a distinct competitive position in the marketplace. These questions do not imply the need for formal planning departments, specific planning cycles, or a specified way of visualizing the future. They do not imply that all your improvements could or should be planned in advance. An effective improvement system combines improvements of many types and degrees of involvement. This requires clear strategic guidance, particularly when improvement alternatives, including major change or innovation, compete for limited resources. In most cases, setting priorities depends heavily on a cost, opportunity, and threat rationale; however, you might also have critical requirements, such as specific student learning or support needs, or societal contributions, that are not driven by cost considerations alone.

2.1 Strategy Development

Purpose

This item asks how you establish a strategy to address your organization’s challenges and threats and leverage its advantages and opportunities, and how you make decisions about outsourcing, work systems, and core competencies. It also asks about your key strategic objectives and their related goals. The aim is to strengthen your overall performance, competitiveness, and future success.

Commentary

A context for strategy development. This item calls for basic information on the planning process and for information on all key influences, risks, challenges, and other requirements that might affect your organization’s future opportunities and directions—taking as long term a view as appropriate and possible from the perspectives of your organization, the education sector, and your marketplace. This approach is intended to provide a thorough and realistic context for developing a student-, other customer-, and market-focused strategy to guide ongoing decision making, resource allocation, and overall management. Such an approach should consider rapid change with the need for agility, adaptation, and innovation.

A future‐oriented basis for action. This item is intended to cover all types of education organizations, competitive/collaborative situations, strategic issues, planning approaches, and plans. The questions explicitly call for a future‐oriented basis for action. Even if your organization is seeking to create an entirely new educational program or service or business, and/or to reinvent or transform itself, you still need to set and test the objectives that define and guide critical actions and performance. Some organizations may find a need to lead/plan for constant reinvention, reflecting and acting swiftly as the education sector evolves, and building resilient systems to “bounce forward” after disruptions.

Competitive leadership. This item emphasizes competitive leadership in educational programs and services, which usually depends on operational effectiveness; educational organizations might compete in the marketplace in which they provide educational programs and services as well as in marketplaces serving online students around the world. Competitive leadership requires a view of the future that includes not only the markets or segments in which you provide educational programs and services but also how you compete and collaborate in providing services. How to compete and collaborate presents many options and requires that you understand your organization’s and your competitors’ and collaborators’ strengths and weaknesses. Deciding how to compete and collaborate also involves decisions on taking intelligent risks in order to gain or retain market leadership. Although no specific time horizons are included, the thrust of this item is sustained competitive leadership.

Data and information for strategic planning. Data and information may come from a variety of internal and external sources and in a variety of forms, and they are available in increasingly greater volumes and at greater speeds. The ability to capitalize on data and information, including large datasets (“big data”), is based on the ability to analyze the data, draw conclusions, and pursue actions, including intelligent risks.

Integration of data from all sources is a key consideration to generate strategically relevant information. Data and information might relate to student/other customer/market requirements, expectations, opportunities, and risks; financial, societal, ethical, regulatory, technological, security and cybersecurity, and other potential opportunities and risks; your core competencies; the competitive environment and your performance now and in the future relative to competitors and comparable organizations; a service line life cycle; workforce and other resource needs; your ability to capitalize on diversity and promote equity and inclusion; your ability to prevent and respond to disasters and emergencies; opportunities to redirect resources to higher-priority services or areas; changes in the local, national, or global economy; requirements for and strengths and weaknesses of your partners and supply network; changes in your parent organization; and other factors unique to your organization.

Blind spots. Blind spots arise from incorrect, incomplete, obsolete, or biased assumptions or conclusions that cause gaps, vulnerabilities, risks, or weaknesses in your understanding of the competitive environment and strategic challenges your organization faces. Blind spots may arise from new or replacement offerings or business models coming from inside or outside the education sector.

Managing strategic risk. Your decisions about addressing strategic challenges, changes in your regulatory and external environment, blind spots in your strategic planning, and gaps in your ability to execute the strategic plan may give rise to organizational risk, including from sustainability, geopolitical, and supply network challenges. Analysis of these factors is the basis for managing strategic risk in your organization.

Work systems. Work systems are the coordinated combination of internal work processes and external resources you need to develop and produce services, deliver them to your students and other customers, and succeed in your marketplace. External resources might include partners, suppliers, collaborators, competitors, students and other customers, and other entities or organizations that are part of your organizational ecosystem. Decisions about work systems involve protecting intellectual property, capitalizing on core competencies, and mitigating risk.

Efficient and effective work systems require

- effective design;

- a prevention orientation;

- linkage to students, other customers, suppliers, partners, and collaborators;

- a focus on value creation for all key stakeholders; operational performance improvement; cycle time reduction; and evaluation, continuous improvement, innovation, and organizational learning; and

- regular review to evaluate the need for fundamental changes in the way work is accomplished.

Work systems must also be designed in a way that allows your organization to be agile and protect intellectual property. In the simplest terms, agility is the ability to adapt quickly, flexibly, and effectively to changing requirements. Depending on the nature of your strategy and markets, agility might mean the ability to change rapidly from one program or service to another, respond rapidly to changing demands or market conditions, or produce a wide range of customized services. Agility and protection of intellectual property also increasingly involve decisions to outsource, agreements with key suppliers, and novel partnering arrangements.

Ecosystems. Organizations should view the ecosystem strategically. They need to be open to new partnership arrangements, consortia, value webs, and organizational models that support the organization’s vision and goals. The organization’s growth may depend on the collective growth of the ecosystem and its ability to prepare for the future. And as competition comes from organizations in different sectors, organizations may be able to stand out from their competitors through new and novel offerings, possibly through the ecosystem. Your strategy should consider your role and your desired role within the ecosystem (as a partner, collaborator, supplier, competitor, or customer—or several of these).

Strategic objectives. To remain competitive and relevant, organizations face both the opportunity and the challenge to focus on the vital few areas that will create impact; your strategic objectives should reflect these vital few. Focusing on the vital few also might mean focusing on competitive advantage and on what your organization does best; for other areas, partnerships and collaborations might be a better use of resources.

Strategic objectives might address rapid response; customization of educational programs and services; partnerships; workforce capability and capacity; specific joint ventures; rapid or market-changing innovation; integrated technology systems; International Organization for Standardization (ISO) quality or environmental systems registration; societal contributions or leadership; social media and digital management of relationships with suppliers, students, and other customers; and program and service quality enhancements.

2.2 Strategy Implementation

Purpose

This item asks how you convert your strategic objectives into action plans to accomplish those objectives, and how you assess progress on these action plans. The aim is to ensure that you deploy your strategies successfully and achieve your objectives.

Commentary

Developing and deploying action plans. With strategy comes identification of a focused set of action plans (priorities), which must include a process for action plan modification, if necessary. Accomplishing action plans requires resources and performance measures, as well as alignment among the plans of your departments/work units, suppliers, and partners. Of central importance is how you achieve alignment and consistency—for example, via work systems, work processes, and key measurements. Also, alignment and consistency provide a basis for setting and communicating priorities for ongoing improvement activities—part of the daily work of all departments/work units. Action plan implementation and deployment may require agility through modifications in organizational structures and operating modes. The success of action plans benefits from visible short-term wins as well as long-term actions.

Performing analyses to support resource allocation. You can perform many types of analyses to ensure that financial resources are available to support the accomplishment of your action plans while you meet current obligations, as well as support ethical/equitable resource allocation. For current operations, these efforts might include the analysis of cash flows, net income statements, and current liabilities versus current assets. For investments to accomplish action plans, the efforts might include analysis of discounted cash flows, return on investment (ROI), or return on invested capital.

Analyses also should evaluate the availability of people and other resources to accomplish your action plans while continuing to meet current obligations. Financial resources must be supplemented by capable people and the necessary facilities and support.

The specific types of analyses performed will vary from organization to organization. These analyses should help you assess the financial viability of your current operations and the potential viability of and risks associated with your action plan initiatives.

Creating workforce plans. Action plans should include human resource or workforce plans that are aligned with and support your overall strategy. Examples of possible plan elements are

- a redesign of your work organization and jobs to increase workforce empowerment and decision making;

- education and training initiatives, such as developmental programs for future leaders, upskilling and training programs on new technologies important to the future success of your workforce and organization;

- enhancement of technology-based learning approaches;

- initiatives to promote greater labor‐management cooperation, such as union partnerships;

- consideration of the impacts of outsourcing on your current workforce and initiatives;

- initiatives to prepare for future workforce capability and capacity needs;

- initiatives to foster knowledge sharing and organizational learning;

- modification of your compensation and recognition systems to recognize team, organizational, customer, or other performance attributes;

- formation of partnerships with the business community to support workforce development; and

- introduction of performance improvement initiatives.

Projecting your future environment. An increasingly important part of strategic planning is projecting the future competitive and collaborative environment. This includes the ability to project your own future performance, as well as that of your competitors. Such projections help you detect and reduce competitive threats, shorten reaction time, and identify opportunities. Depending on your organization’s size and type, the potential need for new core competencies, external factors (e.g., changing requirements brought about by education mandates, instructional technology, or changing demographics), internal factors (e.g., faculty and staff capabilities and needs), and, as appropriate, the pace of change and competitive parameters (e.g., price, costs, or the innovation rate), you might use a variety of modeling, scenarios, or other techniques and judgments to anticipate the competitive and collaborative environment.

Projecting and comparing your performance. Projections and comparisons in this item are intended to improve your organization’s ability to understand and track dynamic, competitive performance factors. Projected performance might include changes resulting from the addition or termination of programs, entry into new markets, the introduction of new technologies, program or service innovations, or other strategic thrusts that might involve a degree of intelligent risk.

Through this tracking, you should be better prepared to consider your organization’s rate of improvement and change relative to that of competitors or comparable organizations and relative to your own targets or stretch goals. Such tracking should serve as a key diagnostic tool for you to use in deciding to start, accelerate, or discontinue initiatives and to implement needed organizational change.

Customers (Category 3)

This category asks how you engage students and other customers for long‐term marketplace success, including how you listen to them, serve and exceed their expectations, build relationships with them, and enhance the customer experience.

The category stresses customer engagement as an important outcome of an overall learning and performance excellence strategy. Your satisfaction and dissatisfaction results for students and other customers provide vital information for understanding them and understanding the marketplace. In many cases, the voice of the customer provides meaningful information not only on your students’ and other customers’ views but also on their marketplace behaviors and on how these views and behaviors may contribute to your organization’s current and future success.

The Education Criteria refer specifically to students in order to stress their importance to education organizations. The Criteria also refer to other customers to ensure that your customer focus and performance management system include all customers. Other customers might include parents, local businesses, the next school to receive your students, and future employers of your students. For-profit institutions might consider shareholders as other customers because of the importance of maintaining their confidence. A key challenge to education organizations may be balancing the differing expectations of students and other customers.

3.1 Customer Listening

Purpose

This item asks about your processes for listening to your students and other customers and determining customer groups and segments. It also asks about your processes for determining and customizing program and service offerings that serve your students, other customers, and markets. The aim is to capture meaningful information in order to meet and exceed your students’ and other customers’ expectations.

Commentary

Customer listening. Selection of voice‐of‐the‐customer strategies depends on your organization’s key business factors. Most organizations listen to the voice of the customer via multiple modes. Some frequently used modes include surveys or feedback information, focus groups with students and other key customers, close integration with key student and other customer groups, interviews with lost and potential students and other customers about their purchasing or relationship decisions, comments posted on social media by students and other customers, win/loss analysis relative to competitors and other organizations providing similar educational programs and services, and survey or feedback information.

Actionable information. This item emphasizes how you obtain actionable information from customers. Information is actionable if you can tie it to key programs, services, and processes, and use it to identify opportunities for new or improved services to better serve your students, other customers, and markets.

Listening/learning and business strategy. In a rapidly changing technological, competitive, economic, and social environment, many factors may affect students’ and other customers’ expectations and loyalty, as well as your interface with students and other customers. This makes it necessary to continually listen and learn. To be effective, listening and learning need to be closely linked with your overall organizational strategy.

Social media. Effective use of social media has become a significant factor in student and other customer engagement, and ineffective use can be a driver of disengagement and relationship deterioration or destruction. Students and other customers are increasingly turning to social media to voice their impressions of your programs, services, and support. They may provide this information through social interactions you mediate or through independent or student- and other customer‐initiated means. All of these can be valuable sources of information for your organization. Negative commentary can be a valuable source for improvement, innovation, and immediate service recovery. Organizations need to become familiar with vehicles for monitoring and tracking this information. Social media are also a means of communication, outreach, and engagement.

Customer and market knowledge. Knowledge of students, student groups, other customers and customer groups, market segments, former students and other customers, and potential students and other customers allows you to tailor programs and services, support and tailor your marketing strategies, develop a more student- and other customer-focused workforce culture, develop new educational programs and services, evolve your brand image, and ensure long-term organizational success.

3.2 Customer Engagement

Purpose

This item asks about your processes for building relationships with students and other customers and for enhancing the customer experience. This includes enabling them to seek information and support, managing complaints, and ensuring that you treat students and other customers fairly. The item also asks how you determine student and other customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. The aim of these efforts is to build a more student- and other customer‐focused culture and enhance loyalty.

Commentary

Engagement as a strategic action. Customer engagement is a strategic action aimed at achieving such a degree of loyalty that the student or other customer will advocate for your brand and your programs and services. Achieving such loyalty requires a student- and other customer-focused culture in your workforce based on a thorough understanding of your organizational strategy and your students’ and other customers’ behaviors and preferences.

Customer relationship and customer experience strategies. A relationship strategy may be possible with some students and other customers but not with others. The relationship strategies you do have may need to be distinctly different for each student group, customer group, and market segment. They may also need to be distinctly different during the different stages of students’ and other customers’ relationships with you. Building relationships might include developing transformational partnerships or alliances with students and other customers across all of the stages of their involvement with your organization—rather than just a transactional-only experience. Relationship stages might include relationship building, the active relationship, and a follow-up strategy, as appropriate.

Brand management. Brand management is aimed at positioning your educational programs and services in the marketplace. Effective brand management leads to improved brand recognition and customer loyalty. Brand management is intended to build students’ and other customers’ emotional attachment for the purpose of differentiating yourself from the competition and building loyalty.

Student and other customer support. The goal of support is to make your organization easy to do business with and responsive to your students’ and other customers’ expectations.

Complaint management. Complaint aggregation, analysis, and root-cause determination should lead to effective elimination of the causes of complaints and to the setting of priorities for process and service improvements. Successful outcomes require effective deployment of information throughout your organization. Your management of complaints might enable you to recover your students’ and other customers’ confidence, enhance their experience, and avoid similar complaints in the future.

Equity (fair treatment). Increasingly, students, other customers, stakeholders, faculty, staff members, communities, partners, collaborators, and stakeholders expect organizations to treat all student segments fairly and to avoid inappropriate discrimination. Meeting these expectations builds trust among citizens, communities, and institutions.

Determining customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. You might use any or all of the following to determine student and other customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction: surveys, formal and informal feedback, dropout and absenteeism rates, student conflict data, complaints, and student referral rates. You might gather information on the web, through personal contact or a third party, or by mail.

Customers’ satisfaction with competitors. A key aspect of determining students’ and other customers’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction is determining their comparative satisfaction with competitors, competing or alternative offerings, and/or organizations providing similar programs and services. Such information might be derived from published data or independent studies. The factors that lead to student and other customer preference are critically important in improving the delivery of educational programs and support services, creating a climate conducive to learning for all students, and understanding the factors that potentially affect your organization’s longer‐term competitiveness and success.

Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management (Category 4)

In the simplest terms, category 4 is the “brain center” for the alignment of your operations with your strategic objectives. It is the main point within the Education Criteria for all key information on effectively measuring, analyzing, reviewing, and improving performance and managing organizational knowledge to drive improvement, innovation, and organizational competitiveness. Central to this use of data and information are their quality and availability. Furthermore, since information and knowledge management might themselves be primary sources of competitive advantage and productivity growth, this category also includes such strategic considerations.

4.1 Measurement, Analysis, Review, and Improvement of Organizational Performance

Purpose

This item asks how you select and use data and information for performance measurement, analysis, and review in support of organizational planning and performance improvement. The item serves as a central collection and analysis point in an integrated performance measurement and management system that relies on financial and other data and information. The aim of performance measurement, analysis, review, and improvement is to guide your organization toward the achievement of key organizational results and strategic objectives, anticipate and respond to rapid or unexpected organizational or external changes, and identify internal and external best practices (including out-of-industry best practices) to share.

Commentary

Alignment and integration of your performance measurement system. Alignment and integration are key concepts for successfully implementing and using your performance measurement system. The Education Criteria view alignment and integration in terms of how widely and how effectively you use that system to meet your needs for organizational performance assessment and improvement and to develop and execute your strategy. (For the purposes of regional and professional accreditation and certification, such assessments might include direct and indirect measures, and qualitative and quantitative data and information.)

Alignment and integration include how measures are aligned throughout your organization and how they are integrated to yield organization‐wide data and information that support fact-based decisions. Organization-wide data and information are key inputs to organizational performance reviews and strategic decision making. These data and information should be used to set and align organizational directions and resource use at the work unit, key process, department, and organization levels. Alignment and integration also include how your senior leaders deploy performance measurement requirements to track departmental, workgroup, and process‐level performance on key measures that are targeted for their organization‐wide significance or for improvement.

Big data. The challenge, and the potential, of ever-increasing amounts of and modalities for data lie in choosing, synthesizing, analyzing, and interpreting both key quantitative and key qualitative data, turning them into useful information, and then acting operationally and strategically. This requires not just data, but knowledge, insight, and a mindset for intelligent risk taking and innovation.

Information analytics. Analysis may involve digital data analytics and data science techniques that detect patterns in large volumes of data and interpret their meaning. For operational improvement, analysis of data comparing two important measurement dimensions (e.g., cost per student, student learning outcomes, student and other customer satisfaction characteristics and their relative importance, retention and completion rates, student default rates, employment rates after degree completion) is usually sufficient. A third dimension, such as time or segmentation (e.g., by student and other customer segments), might be added. In the strategic domain, more advanced information analytics can provide a three-dimensional image, with a fourth dimension of current state and desired or predicted future states of organizational performance, technologies, people, and markets served. From those data-based, fact-based pictures, organizations can develop strategy or strategic scenarios.

The case for comparative data. The use of comparative data and information is important to all organizations. The major premises for their use are the following:

- Your organization needs to know where it stands relative to competitors and to best practices.

- Comparative information and information obtained from benchmarking often provide the impetus for significant (“breakthrough”) improvement or transformational change.

- Comparing performance information frequently leads to a better understanding of your processes and their performance.

- Comparative performance projections and competitors’ performance may reveal organizational advantages, as well as challenge areas where innovation is needed.

Comparative information may also support business analysis and decisions relating to core competencies, partnering, and outsourcing.

Selection of comparative data. Effective selection of comparative data and information requires you to determine needs and priorities and to establish criteria for seeking appropriate sources for comparisons—from within and outside the education sector and your markets. Role-model organizations look for national benchmarks that identify top-10% or top-quartile performance, as appropriate, rather than comparisons to national averages.

Comparative data might include data from similar organizations or education benchmarks. Local or national sources of such data might include

- other organizations through sharing or contributing to external reference databases (e.g., data-sharing consortia, scholarly research projects, white papers, and dissertations);

- the open literature (e.g., outcomes of research studies and practice guidelines); and

- independent organizations that gather and evaluate data (e.g., external surveys, database studies such as the National Study on Instructional Costs and Productivity, survey organizations, accrediting organizations, and agencies or commissions granting professional certification).

Performance review. The organizational review called for in this item is intended to cover all areas of performance. This includes not only current performance but also how you project your future performance. The expectation is that the review findings will provide a reliable means to identify both improvements and opportunities for innovation that are tied to your key objectives, core competencies, and measures of success. Review findings may also alert you to the need for transformational change in your organization’s structure, services, and work systems. Therefore, an important component of your organizational review is the translation of the review findings into actions that are deployed throughout your organization and to appropriate suppliers, partners, collaborators, and key customers.

Use of comparative data in reviews. Effective use of comparative data and information allows you to set stretch goals and promote major nonincremental (“breakthrough”) improvements in areas most critical to your competitive strategy.

Performance analysis. Analyses that you conduct to gain an understanding of performance and needed actions may vary widely depending on your organization’s type, size, competitive environment, and other factors. Here are some examples of possible analyses:

- Trends in formative and summative student assessment results, disaggregated by student segments, as appropriate

- Trends in key operational performance indicators, such as productivity, student learning, waste reduction, and introduction of new or changed programs or services

- Trends in key indicators of student engagement, such as absenteeism, dropout rates, use of educational programs and services, and time to degree completion

- The relationship among student experiences, outcomes, and program persistence and completion

- The relationship among student experiences, outcomes, and postprogram outcomes, such as in other schools or the workplace

- The relationship between student demographics and outcomes

- The relationship between students’ use of learning technologies and facilities and students’ performance

- The percentage of students attaining licenses, industry-recognized certifications, or other professional credentials

- Student participation and achievement in advanced placement courses

- Activity-level cost trends in organizational operations

- Cost trends relative to comparable organizations or competitors

- Cost and budgetary implications of student- and other customer-related problems and effective problem resolution

- Cost and budgetary implications of workforce‐related problems and effective problem resolution

- Cost and budgetary implications of new market entry, including expansion of educational programs and services, and of changing educational and operational needs

- Budgetary and financial impacts of student and other customer loyalty

- Net earnings or savings derived from improvements in quality, operational, and workforce performance (e.g., improvements in workforce capacity, safety, absenteeism, and turnover)

- Comparisons among organizational units showing how quality and operational performance affect budgetary and financial performance

- Relationships among program and service quality, operational performance indicators, and overall financial performance trends as reflected in indicators such as operating costs, budget, asset utilization, and value added per faculty/staff member

- Individual or aggregate measures of productivity and quality relative to comparable organizations’ or competitors’ performance

- How educational program and service improvements or new programs and services correlate with key student and other customer indicators, such as satisfaction, loyalty, and market share

- Interpretation of market changes in terms of gains and losses in students and other customers and changes in their engagement

- Contributions of improvement activities to cash flow, working capital use, and shareholder value

- Allocation of resources among alternative improvement projects based on cost/benefit implications or environmental and societal impact

- Return on investment for intelligent risks that you pursue

- The relationship between knowledge management and innovation

- How the ability to identify and meet workforce capability and capacity needs correlates with retention, motivation, and productivity

- Benefits and costs associated with improved organizational knowledge management and sharing

- Benefits and costs associated with workforce education and training

- Relationships among learning by workforce members, organizational learning, and the value added per employee

Alignment of analysis, performance review, and planning. Individual facts and data do not usually provide an effective basis for setting organizational priorities. This item emphasizes the need for close alignment between your analysis and your organizational performance review and between your performance review and your organizational planning. This ensures that analysis and review are relevant to decision making and that decisions are based on relevant data and information. In addition, your historical performance, combined with assumptions about future internal and external changes, allows you to develop performance projections. These projections may serve as a key planning tool.

Understanding causality. Action depends on understanding causality among processes and between processes and results. Process actions and their results may have many resource implications. Organizations have a critical need to provide an effective analytical basis for decisions because resources for innovation and improvement are limited.

4.2 Information and Knowledge Management

Purpose

This item asks how you build and manage your organization’s knowledge assets and ensure the quality and availability of data and information. This item also asks about your cybersecurity management approach and your organization’s pursuit of innovation. The aim of this item is to improve organizational efficiency and effectiveness.

Commentary

Information management. Managing information can require a significant commitment of resources as the sources of data and information grow dramatically. The continued growth of information within organizations’ operations—as part of organizational knowledge networks, through the web and social media, in organization-to-organization and organization-to-customer communications, and in digital communication/information transfer—challenges organizations’ ability to ensure reliability and availability in a user‐friendly format. In addition, the ability to blend and correlate disparate types of data, such as video, text, and numbers, provides opportunities for a competitive advantage.

Data and information availability. Data and information are especially important in organizational networks, partnerships, and supply networks. You should consider this use of data and information and recognize the need for rapid data validation, reliability assurance, and security, given the frequency and magnitude of digital data transfer and the challenges of cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity. Given the frequency and magnitude of digital data transfer and storage, the prevalence of cybersecurity attacks, and customer and organizational requirements around securing assets and information, managing cybersecurity is an essential component of operational effectiveness. Proper management of cybersecurity requires a systems approach that focuses on using key organization factors to guide cybersecurity activities and integrating cybersecurity with your overall leadership and management approaches. In a dynamic and challenging environment of new threats, risks, and solutions, managing cybersecurity means considering your organization’s unique threats, vulnerabilities, and risk tolerances. It means determining activities that are important to critical service delivery and to your students and other customers, and prioritizing investments to protect them. Cybersecurity may involve training workforce members not directly involved in information technology matters and educating students, other customers, suppliers, and partners. It may also involve communicating with these stakeholders to inform them of potential cyber threats, inform them of breaches, and report recovery efforts in order to maintain their confidence in your organization.

Many sources for general and industry-specific cybersecurity standards and practices are referenced in the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST’s) Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. The Baldrige Cybersecurity Excellence Builder is a self-assessment tool incorporating the concepts of the NIST cybersecurity framework and the Baldrige systems perspective.

Knowledge management and organizational learning. One of the many issues facing organizations today is how to manage, use, evaluate, and share their ever‐increasing organizational knowledge. Leading organizations benefit from the knowledge assets of their faculty, staff, students, other customers, suppliers, collaborators, and partners, who together drive organizational learning and innovation.

Knowledge management should focus on the knowledge that your people need to do their work; improve processes, programs, and services; and innovate to add value for students, other customers, and your organization. Your organization’s knowledge management system should provide the mechanism for sharing your people’s and your organization’s explicit knowledge (facts, figures, data, and information in documents and other repositories) and implicit knowledge (knowledge personally retained by faculty and staff) to ensure that high performance is maintained through transitions. You should determine what knowledge is critical for your operations and then implement systematic processes for sharing this information. This is particularly important for implicit knowledge.

Effective knowledge management requires clear roles and responsibilities, a culture of knowledge sharing, systematic processes for sharing knowledge and expertise, the identification and management of core knowledge assets, and tools (including technology) that are appropriate for your organization.

Pursuit of innovation. In an organization that has a supportive environment for innovation, there are likely to be many more ideas than the organization has resources to pursue. This leads to two critical decision points in the innovation cycle: (1) commensurate with resources, prioritizing opportunities to pursue those opportunities with the highest likelihood of a ROI (intelligent risks), and (2) knowing when to discontinue projects and reallocate the resources either to further development of successful projects or to new projects. To make decisions and allocate resources, you might use various types of forecasts, projections, options, scenarios, knowledge, analyses, or other approaches to envisioning the future. Careful evaluation of your many potential opportunities for innovation is critical for determining which ones might provide breakthrough change for your organization.

Workforce (Category 5)

This category addresses key workforce practices—those directed toward creating and maintaining a high‐performance environment and toward engaging your workforce.

To reinforce the basic alignment of workforce management with overall strategy, the Criteria also cover workforce planning as part of overall strategic planning in category 2.

5.1 Workforce Environment

Purpose

This item asks about your workforce capability and capacity needs, how you meet those needs to accomplish your organization’s work, and how you ensure a supportive workplace climate. The aim is to build an effective environment for accomplishing your work and supporting your workforce.

Commentary

Workforce capability vs. workforce capacity. Many organizations confuse the concepts of capability and capacity by adding more people with incorrect skills to compensate for skill shortages, or by assuming that fewer highly skilled people can meet capacity needs for processes requiring less skill or different skills but more people to accomplish. Having the right number of workforce contributors with the right skill set is critical to success. Looking ahead to predict those needs for the future allows for adequate training, hiring, relocation times, and preparation for work system changes.

Workforce change. Managing change for your workforce involves organizational change controlled and sustained by leaders. It requires dedication, involvement of faculty and staff at all levels, and constant communication, especially during periods of workforce growth or shortages. Change is strategy-driven and stems from the top of the organization, and it requires the active engagement of the whole organization.

Workforce support. Most organizations, regardless of size, have many opportunities to support their workforce. Some examples of services, facilities, activities, and other opportunities are flexible work hours, workplaces, and benefits packages; child and elder care; special leave for family responsibilities and community service; personal and career counseling; career development and employability services; recreational or cultural activities; on‐site health care and other assistance; formal and informal recognition; non‐work‐related education; outplacement services; and retiree benefits, including ongoing access to services.

5.2 Workforce Engagement

Purpose

This item asks about your systems for managing workforce performance and developing your workforce members to enable and encourage all of them to contribute effectively and to the best of their ability. These systems are intended to promote retention, to foster high levels of engagement and performance, to address your core competencies, and to help accomplish your action plans and ensure your organization’s success now and in the future.

Commentary

High performance. The focus of this item is on a workforce capable of achieving high performance. Understanding the characteristics of high-performance work environments, in which people do their utmost for their students’ and other customers’ benefit and the organization’s success, is key to understanding and building an engaged workforce. High performance is characterized by flexibility, innovation, empowerment and personal/team accountability, knowledge and skill sharing, good communication and information flow, alignment with organizational objectives, student and other customer focus, and rapid response to changing organizational needs and market requirements.

Workforce engagement. Many studies have shown that high levels of workforce engagement have a significant, positive impact on organizational performance. Research has indicated that engagement is characterized by performing meaningful work; having clear organizational direction and accountability for performance; and having a safe, trusting, effective, and cooperative work environment. In many organizations, staff members and volunteers are drawn to and derive meaning from their work because it is aligned with their personal values.

Drivers of workforce engagement. Although satisfaction with pay and pay increases are important, these two factors generally are not sufficient to ensure workforce engagement and high performance. Some examples of other factors to consider are effective problem and grievance resolution; development and career opportunities; the work environment and management support; workplace safety and security; the workload; effective communication, cooperation, and teamwork; the degree of empowerment; job security; appreciation of the differing needs of diverse workforce groups; and organizational support for serving students and other customers.

Factors inhibiting engagement. It is equally important to understand and address factors inhibiting engagement. You could develop an understanding of these factors through workforce surveys, focus groups, blogs, or exit interviews with departing faculty and staff.

Compensation and recognition. As part of performance management, compensation and recognition systems should be matched to your work systems. Recognition can include monetary and nonmonetary, formal and informal, and individual and group mechanisms. To be effective, compensation and recognition might include promotions and bonuses tied to performance, demonstrated skills, peer evaluations, collaboration among departments, skills acquired, adaptation to new work systems and culture, and other factors. Approaches might also include profit sharing; mechanisms for expressing simple “thank yous”; rewards for exemplary team or unit performance; and linkage to student or other customer engagement measures, achievement of organizational strategic objectives, or other key organizational objectives. Recognition systems for volunteers who contribute to the organization’s work should be included, as appropriate.

Other indicators of workforce engagement. In addition to direct measures of workforce engagement through formal or informal surveys, other indicators can be tracked to assess a lack of workforce satisfaction and engagement. These measures include absenteeism, turnover, grievances, and strikes.

Performance development. Education organizations today need faculty and staff members who are versatile and who can continually upgrade their work skills. High-performing organizations address this need by meeting faculty and staff members’ rising expectations for career-relevant learning and development, as well as succession planning. In performance development, faculty and staff members pursue personal growth and growth in the organization through both internal and external learning. This learning involves engaging work assignments, opportunities, and personal learning to reach the next level of organizational and personal performance.

Performance development needs. Depending on the nature of your organization’s work, workforce responsibilities, and stage of organizational and personal development, workforce development needs might vary greatly. These needs might include training in communication and processes to prevent student harm; training in the science of safety; gaining skill for knowledge sharing, communication, teamwork, and problem solving; interpreting and using data; exceeding students’ and other customers’ requirements; analyzing and simplifying processes; reducing waste and cycle time; working with and motivating volunteers; and setting priorities based on strategic alignment or cost‐benefit analysis.

Education needs might also include advanced skills in new technologies or basic skills, such as reading, writing, language, arithmetic, and computer skills.

Operations (Category 6)

This category asks how you design, manage, and improve your organization’s work, educational program and service design and work processes; ensure operational effectiveness to deliver student and other customer value; manage your supply chain and mitigate risks; and achieve organizational success now and in the future.

6.1 Work Processes

Purpose

This item asks about the design, management, and improvement of your key educational programs and services and your work and support processes.

Commentary

Product and/or service design. Your design approaches might differ appreciably depending on the nature of your educational program and offerings—whether they are entirely new, are variants, are customized, or involve major or minor work process changes—but also on the size and complexity of the organization. Designing programs and services should be centered on student and other customer key requirements.

Effective design must also consider the cycle time and productivity of production and delivery processes. This might involve detailed mapping of service delivery processes and the redesign (“reengineering”) of those processes to achieve efficiency, as well as to meet changing student and other customer requirements.

Work processes. Your key work processes include your program- and service‐related processes and those business processes that your senior leaders consider important to organizational success and growth. These processes frequently relate to your organization’s core competencies, strategic objectives, and critical success factors. Key business processes might include technology acquisition, information and knowledge management, supply-network management, supplier partnering, outsourcing, mergers and acquisitions, project management, and sales and marketing. For some nonprofit organizations, key business processes might include fundraising, media relations, and public policy advocacy. Given the diverse nature of these processes, the requirements and performance characteristics might vary significantly for different processes.

Process design. Many organizations need to consider requirements for suppliers, partners, and collaborators at the work process design stage. Overall, effective design must consider all stakeholders in the value chain. If many design projects are carried out in parallel, or if your organization’s educational programs and services share people, equipment, or facilities that are used for other services, coordination of resources might be a concern, but it might also offer a means to significantly reduce costs and time to design and implement new programs and services.

Factors that you might need to consider in work process design include safety, long-term performance, measurement capability, process capability, variability in student and other customer expectations requiring support options, supplier capability, and documentation.

In‐process measures. As part of process implementation, this item refers specifically to in‐process measurements. These measurements require you to identify critical points in processes for measurement and observation. These points should occur as early as possible in processes to minimize problems and costs that may result from deviations from expected performance.

Process performance. Achieving expected process performance frequently requires setting in‐process performance levels or standards to guide decision making. When deviations occur, corrective action is required to restore the performance of the process to its design specifications. Depending on the nature of the process, the corrective action could involve technology, people, or both. Proper corrective action involves changes at the source (root cause) of the deviation and should minimize the likelihood of this type of variation occurring again or elsewhere in your organization.

When interactions with students or other customers are involved, evaluation of how well the process is performing must consider differences among students and other customer groups. This might entail allowing for specific or general contingencies, depending on the student or other customer information gathered. In some organizations, cycle times for key processes may be a year or longer, which may create special challenges in measuring day‐to‐day progress and identifying opportunities for reducing cycle times, when appropriate.

Support process requirements. Support process requirements do not usually depend significantly on program and service characteristics. Such requirements usually depend significantly on internal requirements, and they must be coordinated and integrated to ensure efficient and effective linkage and performance. Support processes might include processes for finance and accounting, facilities management, legal services, human resource services, public relations, and other administrative services.

Process improvement. This item calls for information on how you improve processes to achieve better program, service, and process performance. Better performance means not only better quality from your students’ and other customers’ perspectives but also better budgetary, financial, and operational performance—such as productivity—from your other stakeholders’ perspectives. A variety of process improvement approaches are commonly used. Examples include

- using the results of organizational performance reviews;

- sharing successful strategies across your organization to drive learning and innovation;

- performing process analysis and research (e.g., process mapping, optimization experiments, error proofing);

- conducting technical and business research and development;

- using quality improvement tools like PDSA;

- benchmarking;