Taking Measure

Just a Standard Blog

Answering the Call: How NIST Helps Crime Labs Recover Evidence from Mobile Devices

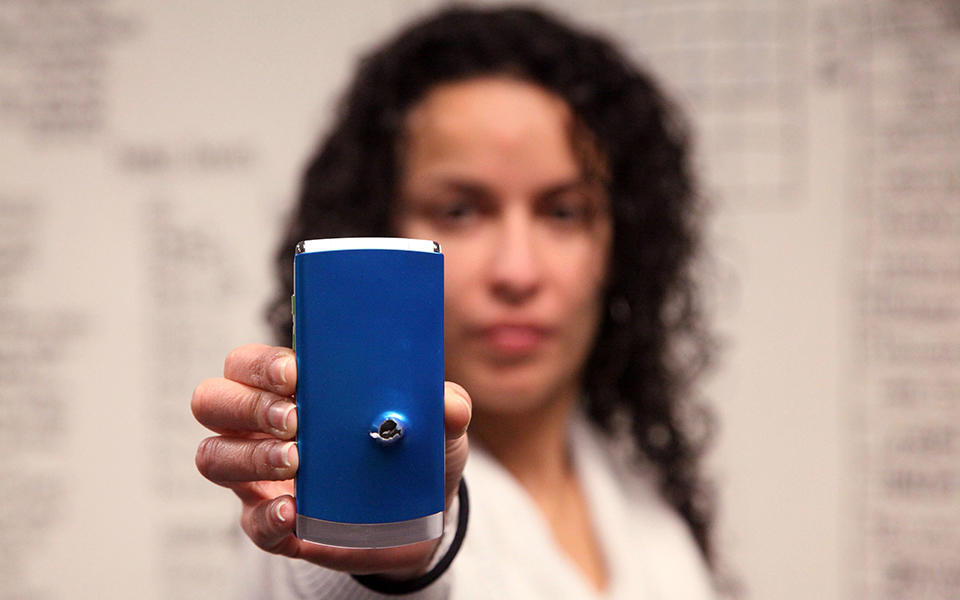

We can recover useful evidence from mobile phone in a variety of damaged conditions, even ones that have been shot with a bullet!

Everyone has a phone these days, even the bad guys. To try to get away with their crimes, lawbreakers sometimes attempt to destroy their phones and the evidence they contain. On TV, computer experts swoop in and almost magically retrieve all sorts of incriminating data from the devices, often in less than an hour. Don’t get me wrong, I like to watch shows such as CSI: Miami, CSI: NY and CSI: Cyber, but have you ever wondered how much of these shows is accurate? Is it really that “easy” to solve crimes, especially ones that involve digital evidence?

A few years after I started working at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), I joined the Computer Forensics Tool Testing (CFTT) program. Imagine how excited I was to learn that I was going to be so close to the kind of work I saw on TV! Soon after I started getting familiar with various tools in the lab, I was using CFTT’s methodology to test general computer forensics tools and mobile forensics tools. That’s the current focus of my research.

Let’s just pause here so I can elaborate a little about what I mean by general computer forensics tools and mobile forensics tools. General computer forensics tools are designed to analyze data mostly from computer hard drives. Mobile forensics tools are tailored to analyze data from different mobile devices including, but not limited to, cellphones and tablets. In case you’re wondering, yes, mobile devices could also include SIM cards, SD cards, GPS units, smartwatches and even drones, but some of these are out of our scope right now.

My research currently focuses on testing a variety of mobile forensic software tools on 40 different mobile devices. The mobile devices we use in our testing include a good mixture of feature/flip phones, tablets and smartphones. This list gets updated approximately every two years to include some of the most popular devices on the market. This does not mean that we update the whole list every two years; it means that every two years, before starting a new round of testing, we may replace only few of the devices as most of them may still be popular. We don’t do the decision-making on our own either. We have a NIST Digital Forensic Steering Committee that also provides guidance regarding the devices and tools we should focus on.

Now, taking this back to TV shows. Did you ever wonder if the forensic tools we actually have work like the ones on TV? After being in this group for a while, I was finally able to see the difference between how it is on TV and how it is in real life. For one thing, it takes a lot longer to analyze a piece of evidence in real life.

Also, while it’s not usually part of the plot, have you ever wondered how forensic labs choose the tools that they use to conduct their investigations? Or how well those tools work for their cases? The truth is forensic labs often don’t have the budget to get multiple tools and must work with what they have or can afford. To help the labs do the best they can with what they’ve got, every time we finish testing a tool, we create a report listing any anomalies (e.g., incomplete text messages, truncated or incomplete contact names) we found. The next step in the process is to discuss the anomalies with the tool’s makers to help them improve their product. We continue the process by making the report publicly available so the forensic community can learn about the tool’s capabilities and limitations. This helps labs to know if the tool they have is the appropriate one for their case or to make informed choices as to what tools to use or buy.

Our forensic tool reports can also be used in court to support the admissibility of digital evidence acquired from mobile devices. This goes back to 1999 when prosecutors were increasingly introducing digital evidence in court but there were no standardized tests to show that the techniques police used for gathering that evidence were forensically sound. As a result of this challenge, CFTT was born in collaboration with other federal agencies to develop a methodology to test the tools in question to make sure that they produced valid results.

But wait, here’s my favorite part: Just like in the TV shows, we can recover information from damaged devices! By damaged I mean water/liquid damage, any physical damage such as shattered screens, being burned or even shot with a bullet! This challenge requires we extract the data using techniques called JTAG and chip-off. Applying either of these techniques requires the devices to be disassembled all the way to the circuit board. For JTAG, I first must identify the test access ports (TAPs) on the board to be able to gain access to the memory chip through its processor. The cool part of this process is that I get to solder thin wires to the TAPs on the circuit board. It can be challenging at times as the TAPs may be tiny, making the soldering more difficult, but at the same time it is fun!

On the other hand, when using the chip-off technique, there is only one requirement. After you properly remove the memory chip from the circuit board — yes, the chip must be off the board and you must be careful not to damage the electrical leads — you only need to have a chip reader that supports the specific model being analyzed.

The testing of these techniques was our latest contribution to the mobile forensic tools testing process. It’s interesting to note that our tests revealed that the techniques were equally effective in returning good results. Developing the chip-off tests was done in collaboration with the Fort Worth Police Department and VTO Labs in Colorado. There is also a web version of our testing methodology available for users to conduct their own NIST-like tests.

The real process certainly has more limitations and considerations, but part of what we do at NIST is help make it possible for digital evidence to be used in court and for police to understand, buy and use mobile forensic tools. It’s great to know that I am one of the people helping law enforcement to put away the bad guys.

About the author

Related Posts

Comments

Hello Ravinder,

You can always contact us at [email protected] or me directly at [email protected]. We would gladly talk to you about the project.

Best, Jenise

Does NIST send DST to atomic clocks? I have one, but it is one hour behind.

Hi Ben!

You can learn more about how to troubleshoot your radio-controlled clock at https://www.nist.gov/pml/time-and-frequency-division/radio-stations/wwv….

Thanks!

Mark

WOW, to be back as an Officer again in our E.T. Unit. Wish I was working with you. I so enjoyed gathering and processing evidence. Always wanted to retire and join the State Lab. However an OJT kept me from applying.

The old addage..."If...."

Great article I can feel your enthusiasm.

Hi Alan,

Thanks a lot for your comment. I agree with you, retiring and doing this kind of work would have been awesome. I truly enjoy it! I'm glad you liked the article and felt the enthusiasm.

Best, Jenise

Wow! Very interesting information and very important in our current culture of technology. Thanks for sharing.

Hi Gretchen,

You are welcome. Thanks for your comment, glad you found it interesting.

Best, Jenise

Jenise, can you elaborate on how well if any of these tools work when data is encrypted at rest. It seem this would be the first issue you have to address being that most if not all phones are now encrypted during user set up if not out the box.

Hello Andre,

Thank you so much for your comment. Encryption is certainly a challenge. For this research, the devices used were not encrypted nor jailbroken or rooted. There is always more to it but I will encourage you to send me an email at [email protected] to continue the conversation. Looking forward to it.

Best, Jenise

Can you explain "jail broken" or "rooted"? Also, can you intercept transmissions from active phones/tablets for analysis without detection? Also, more about the "chip analyzer".

HI Don,

Thank you for your comment. The terms "jailbroken"(used to refer to iOS devices) and "rooted"(used to refer to Android devices) mean the same. When a device has been "jailbroken" or "rooted" means that the user now has privileged access to the Operating System of the device. This allows the user to install applications that are not allowed (by default) by the Operating system among other things.

The techniques used in this research (JTAG/Chip-off) are not used to intercept transmissions from active phones and tablets without detection.

Could you be more specific about what you want to know regarding the chip analyzer? You can always send an email to either [email protected] or [email protected].

Best,

Jenise

I thoroughly enjoyed some these readings. Thank you for the publications.

Thanks a lot for reading it Jennifer.

Good job and it is true.

Thanks Delcia Derrick!

Your area of Research is quite interesting I would like to know more details if is convenient to you.