Standards Success Stories

NIST’s Standard Cigarettes for Fire Safety

Cigarettes are one of the biggest causes of deadly house fires. According to the National Fire Protection Association, one out of every 20 home fires is started by smoking materials.

Throughout its history, NIST has long engaged in efforts to reduce the fire risk of cigarettes. In 1932, the agency introduced a particularly notable invention.

“We have a self-extinguishing cigarette,” says NIST’s Sally Bruce. “And that was a measurement solution, because people were smoking, they'd fall asleep on their couch, and house fires would occur.”

To this day, NIST still produces a self-extinguishing cigarette, known as NIST SRM 1082. Like the original NIST design, NIST 1082 is wrapped in paper containing bands that are less permeable to air than the rest of the cigarette. The bands reduce the amount of air that is available to the burning tobacco. This causes the cigarette to extinguish itself unless the user puffs on it. NIST 1082 serves as a reference material for manufacturers creating their own fire-safe versions; if you look closely at cigarettes today, you’ll notice they also have bands around them.

On the other end of the spectrum, NIST has produced other standard cigarettes — SRM 1196 and its successor 1196a — that are designed to burn strongly. Containing unbanded paper and a longer tobacco column, these cigarettes serve as a strong “ignition source” to test the fire resistance of consumer products and other materials.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission and California law both require the use of NIST 1196a in testing the fire resistance of mattresses, couches and other soft home furnishings.

The LED Lighting Industry

In early 2010, 25% of the electricity in the U.S. went toward creating light. In 2020, it was only about 6%. Why the dramatic decrease? Rooms and other spaces aren’t getting any dimmer; to the contrary, they appear to be better lit than ever.

The answer is LEDs. In just a couple of decades, LED lighting has transformed the world’s technological landscape. White-light LEDs now illuminate our bedrooms, emanate from car headlights, and light up nighttime roads. LED lights have been so readily adopted because they require far less energy than earlier forms of lighting and reduce energy costs.

But how did LED lighting become one of the biggest success stories of 21st-century technology? You guessed it: standards and measurements.

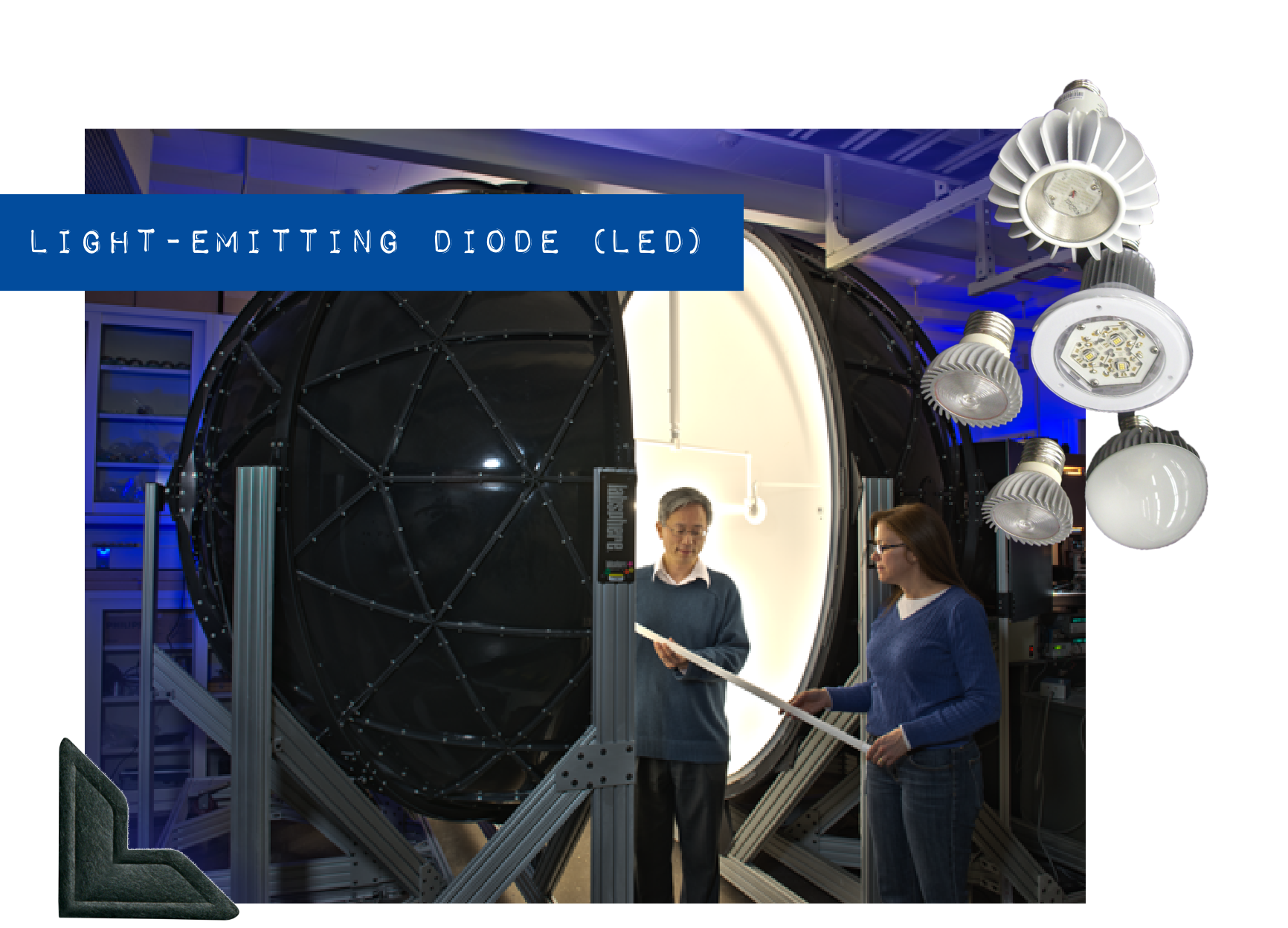

LEDs are produced by what is known as the solid-state lighting industry. Fifteen years ago, industry and government organizations alike were beginning to recognize that “solid state lighting could be transformative,” says Cameron Miller, a NIST researcher who has devoted much of his career to the measurement science of lighting.

In 2006, manufacturers, standards groups, and testing labs came together in a Washington, D.C., meeting organized by the Department of Energy Solid-State Lighting Program.

The LED lighting situation was a mess back then. “You couldn’t compare the LED products that were coming out because they were all being measured differently,” Miller says. So these organizations got to work.

“We were going from incandescent lamps that you hoped would last 2,000 hours to products people were claiming would last over 200,000 hours,” says Miller. “And without a measurement methodology, how do people figure out if this is true or not?”

Several organizations, such as the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) and the International Commission on Illumination (CIE), started working on documentary standards for this new form of lighting. NIST researchers took leadership roles in many of these organizations and served on their technical committees. These new standards helped labs accurately measure such properties as the color of the light, the expected lifetime of LEDs, and the performance of the semiconductor chips that convert electricity to light.

“This was significant,” Miller says, “because now it put everybody on the same footing to be able to measure solid-state lighting products.”

Meanwhile, NIST researchers introduced methods for measuring various properties of LED lights. For example, they developed a new technique for objectively measuring color quality in an LED light through a property known as chromaticity, which describes such things as the light’s hue and saturation.

“So now all this measurement infrastructure was put in place. A lot of that was driven by NIST research on how to make these measurements,” Miller says.

With the industry poised for quick growth, NVLAP set up a program for accrediting labs that perform testing of energy-efficient lighting products. This was urgently needed because the market for LED lighting was exploding and so there was a need for a number of labs to provide capacity for testing the new lighting products that were coming out.

Separate from laboratory accreditation, NIST also created proficiency tests that labs can perform to see how accurate their measurements are. This provides what NIST calls “measurement assurance.”

“We had 118 laboratories participate worldwide in about four years,” Miller says. In one scenario, NIST physically sends out six lamps and compares participants’ measurements to NIST measurements.

If a lab performed poorly on a proficiency test, then it could carry out corrective actions to improve its performance. The results of these proficiency tests are often provided to prospective customers upon request and for future lab accreditation procedures.

NIST also does work in basic science to serve the lighting industry, for example by providing accurate measurements of the candela, one of the fundamental units of the International System of Units (SI).

The candela is the SI’s base unit for photometry — the science of measuring light as perceived by the human visual system.

“Our uncertainty for the measurement of candela is half of what any other national metrology institute can offer right now. It's around 0.2%, where other labs are around 0.5%. And this is all driven by the solid-state lighting industry,” Miller says.

And what we have learned about the human eye continues to inform NIST’s efforts to measure how we respond to light. People are more sensitive to some colors than to others, and this sensitivity changes as day falls into night — and as people get older.

Manufacturers need to take these ideas into account as they design virtually every lighting product on the market, a task that traces all the way back to the candela unit.

Why is all of this important? Solid-state lighting had a global market of $33 billion in 2019 and is projected to reach $74 billion in 2027, according to Allied Market Research. Which means NIST’s standards and measurements continue to play a role in supporting this now-robust and highly successful industry.